An interview with ultra-marathoner Ihor Verys: How to stay resilient when challenging yourself to the limit

Ihor Verys is an ultra-marathon trail runner who regularly wins races through the wilderness that last multiple days and nights. In so doing, he runs hundreds of kilometres at a time, barely eating and sleeping. In a 2023 world championship race, he ran 717 kilometres, over five days and four nights. He finally had to stop, finishing second, because he was so exhausted he became disoriented and couldn’t remember his own name. In another race in 2024 called the Barkley, one of the most brutal of the format, he ran for almost 60 hours through a state park in Tennessee, with no map, finding his way on a barely distinguishable trail, through brambles and damp forest, on a course he had never seen before the race. During that event, he completed elevation changes equivalent to climbing Mt. Everest… twice. Owing to its punishing difficulty, only about twenty people have finished that race since its inception in 1986, and he became the first ever Canadian to do so.

I first heard about Ihor through a friend of mine, John, my former rugby coach who is now the president of a high-performance sport organization in Victoria, BC, called 94 Forward. I called him up asking him if he knew any interesting people in sport who might be willing to sit with me for an interview about their approach to leadership. At the end of the conversation, John said “oh by the way, you gotta meet this guy Ihor.” He told me about his resume. I was impressed, but my first reaction was “well it doesn’t sound like he’s in a leadership role, and I tend to write about and for leaders, but let me think about it.” Two weeks later I called John back and said “I can’t stop thinking about this guy Ihor. Can you send me his contact information?”

I wanted to speak to Ihor is because I was captivated by his ability to challenge himself to the absolute limit of his performance capabilities. I wanted to know what strategies he uses to remain resilient while pursuing the most difficult goals the imagination can conjure. And I wondered if corporate leaders, the kind I work with and write this newsletter for, might be able to learn something from him about how he sustains himself when seeking the limits of human performance.

Ihor was born in Ukraine, and moved to Canada in 2015 to attend Assiniboine College in Brandon, Manitoba. Around that time he started running to cope with the challenges of becoming a foreign student in a new country. Short races grew into longer ones, and only a few years later he progressed to ultra-marathon running. Ultras are any race longer than a typical marathon (which is just over 42 kilometres), though the distances can vary, and sometimes extend to hundreds of kilometres. Since starting his ultra career in 2021 in this serendipitous way, he has realized a staggering amount of success, though his understated, warm, ‘happy warrior’ persona camouflages his stature in the sport. Some of his notable accomplishments are as follows:

- Barkley Marathon (2024): as mentioned, he was the first Canadian to finish this race under the 60 hour time limit (he doesn't know how far he ran because you're not allowed to use GPS trackers in this event);

- HURT 100 (2024): he won this 100 mile race through the tropical rain forest in Hawaii;

- Canadian Death Race (2023): he won this 118 kilometre race in Alberta;

- Sinister 7 (2022): he won this 100 mile race in Alberta;

- Fat Dog 120 (2022): he won this 120 mile race in BC.

In 2024, Ihor won a Best of BC Award from Sport BC. Previous winners included Steve Nash, Christine Sinclair, Carey Price, and Joe Sakic.

Here is a short outline of this article:

- Full-length interview with Ihor Verys (YouTube)

- Key takeaways

- Set a goal to be the best version of yourself

- Fragment large goals into smaller ones

- Preparation makes hard goals seem easier

- You need negative thinking

- The pain cave

- Acceptance

- Recovery contributes to high-performance

- Endurance is a path to ‘becoming’ and ‘meaningfulness’

- Go beyond mere motivation

- The role of ‘fun’ when pursuing difficult goals

- Community supports high-performance

- “We are racing yesterday’s self”

- Rethinking failure

- Ihor’s contact information

- Appendix

Full-length interview with Ihor Verys (YouTube)

Here is the YouTube video of the full-length interview with Ihor.

Please see the notes in the description under the video, for a list of key topics covered and timestamps for each.

This interview was recorded on August 13, 2025.

Please note if I look like a member of the order of the Sith (Star Wars reference) during this interview, it's because we recorded late in the day, and my office window faces west, so I had to pull the blinds to block the glaring sun.

Also you’ll notice a short blip around the 1 hour, 1 minute mark, when my seven year old son pulled my ethernet cable out of the wall. Hopefully the editing smoothed it out!

Full-length interview with Ihor Verys (Aug 13, 2025)

Key takeaways:

Set a goal to be the best version of yourself

Though we’re often taught to set specific, measurable, and achievable goals, Ihor instead often sets a goal to be the very best version of himself, and to push himself to his absolute limit. He’ll set a goal to reach his physical and mental potential, to just run until he can’t run anymore, without knowing what the endpoint will be in terms of time or distance. Though this strategy is a good fit for some of his races, which adopt a ‘last man standing format’ where the race continues until only one person remains, I think it could be useful when pursuing other kinds of difficult goals. Often challenging goals are complex and long term, and the path to achieving them feels endless or at least circuitous. So setting a goal to do nothing but keep going until you can’t go any further, might help motivate you when the end isn’t in sight. Ihor’s logic for using this strategy is persuasive. He said he’s sometimes seen people who set a concrete goal to run a certain distance or duration, reach that arbitrary threshold and then suddenly and unexpectedly quit. But could they have gone further if they adopted a different goal focus?

Fragment large goals into smaller ones

Ihor said that when he runs a really long and hard race, to stay resilient he’ll divide it up into multiple short races. Some of the race formats he competes in nudge him do this naturally - ones called ‘backyard’ races involve running repeated loops of the same distance. You must complete a loop in a certain time, otherwise you’re out. The distances of the loops and time limits aren't demanding at first, but become exponentially harder as the race progresses and fatigue sets in. For Ihor, when the race becomes hard, and focusing on completing the next loop feels daunting, he’ll start "subdividing" the race. He’ll start thinking in terms of 1 hour compartments. Then he may subdivide again, and just run from tree to tree, turn to turn, or driveway to driveway. So one of his key strategies for sustaining motivation is to fragment large goals into smaller ones, and then repeat that process to create progressively smaller and more realistic objectives as needed.

Preparation makes hard goals seem easier

Another strategy Ihor uses to pursue and achieve incredibly hard goals, is engaging in an almost obsessive level of preparation before key races. By doing this he starts to perceive hard goals as easier and more realistic. He says the odds are against you when facing a limit-testing, high-performance goal, so you need to control everything you can about your preparation. Before running the Barkley, there was very little information available about this secretive, invitation-only race. He had never run it before and didn’t know the terrain. And racers don’t receive any details about the course until they arrive on site. So he spent hours scouring Google Earth, trying to understand the topography and possible course route in as much detail as he could. During the interview, I reflected that perhaps when it comes to pursuing high-performance goals, the level of preparation needs to reach a one-to-one ratio with the level of goal difficulty.

You need negative thinking

Ihor says that part of your preparation process, prior to pursuing high-performance goals needs to involve thinking about all that will go wrong. He says many athletes visualize themselves winning a race, and how they will feel at the finish line, to build their motivation. But he says that when pursuing really challenging goals like running an ultra-marathon, things always go wrong, and so you need to map out potential obstacles. What could make you suffer? What are you going to do when something goes sideways? For him this involves preparing for nasty scenarios like the body rejecting food, his legs cramping, or developing blisters. So he suggests including negative, defensive, problem-oriented thinking in any preparation process prior to pursuing difficult goals.

The pain cave

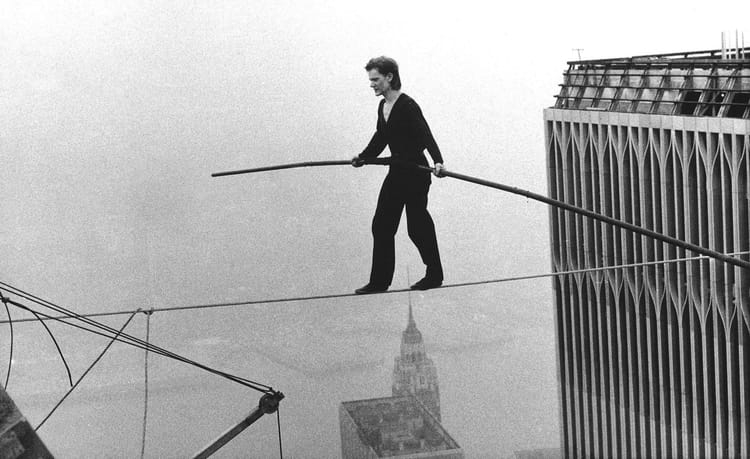

I love this one. Apparently this principle is conventional wisdom among endurance athletes, but I’ve only just discovered it. Ihor says in every long race there will be waves, ups and downs, like a sine wave that you learned about in high school math class (see below). You may start a race with an endorphin high, and that may last for an extended period. But at some point, you will descend into an experiential valley, characterized by, well misery. Your time in the valley will be marked by pain, suffering, and a sharp decrease in motivation. Ihor says this is the ‘pain cave.’ He says a key is to notice when you’re in the pain cave, and to realize that it’s ever-changing, and that at some point, you will emerge from it. Your experience, like the sine wave, is constantly changing. The pain never lasts. So he said you need to ‘surf’ the good times and ride that momentum as long as you can. And when you descend into the dark valley, remind yourself that the experience is impermanent, and will soon end.

I think there’s two valuable ideas here. First, it seems giving your suffering a label helps normalize it, making it seem more controllable. Perhaps by calling the pain cave ‘the pain cave,’ by giving it a name, the experience feels expected, knowable, and therefore manageable.

Another insight is about the impermanence of our experience during challenge, pain and discomfort. When pursuing hard goals, your experience will never be static. This is reassuring in a way. If you’re down, don’t worry, because pain is temporary on any arduous journey, and soon you will emerge from the dark place.

The last thing I learned from Ihor on this theme comes from this quote, where he says “you are going to enter the pain cave… when I’m there I feel like I’m at home. I know how to live there, how to react, and how to get out.” This suggests that the more you expose yourself to pain and discomfort, the more mentally skillful you become at managing it. Perhaps you can 'practice' suffering and improve your ability to endure it.

Acceptance

Ihor says sometimes when he’s racing, one coping strategy he uses is to acknowledge and accept pain when it’s present. He says by accepting it you “turn down the burner” of the sensation.

He said another step he uses when accepting pain, is to ‘shelve it.’ When using the shelving technique, step one is to say “the pain is there, I accept it.” Step two involves saying “I’m going to put this on the shelf for now, and finish this race. When I finish, I’ll pick up the pain and suffer then. For now, I’m putting all the physical pain signals aside.”

I find it interesting that the ‘suppression’ or turning away from the pain, only seems possible AFTER Ihor has taken some steps to accept it. This makes me think there’s something important about the sequencing, about accepting the pain and suffering first, before trying to put it on the shelf.

In this article, I wrote about how acceptance is a useful, evidence-based coping strategy.

Recovery contributes to high-performance

Ihor and I talked briefly about how recovery contributes to high-performance. He feels recovery is important to gain the full benefit from his training (i.e., that’s when you become stronger, better). He said he also counsels other athletes to go into races fully recovered, or even under-trained. Too much accumulated stress, he says, leads to injury. Overall, he feels that pursuing difficult or high-performance goals must coexist with, or live side by side with recovery to generate peak performance.

For a few years I’ve thought that leaders and corporate culture in general could benefit from this perspective. In the interview I said I’ve often observed corporate cultures that move briskly from one task to the next, in a never-ending cycle. I don’t get the impression typical corporate cultures value the notion of strategic rest, or planning out the annual cycle in such a way to provide staff with a fallow period, where they can consolidate energy. I think at the very least companies could make use of ‘100-day plans’ more often, where leaders ask for a high-performance push over a temporary period, and promise a rest and recovery phase afterwards.

In this article, I flirt with the notion that business leaders could plan out when they will challenge their teams, including scheduling strategic periods of recovery.

Endurance as a path to ‘becoming’ and ‘meaningfulness’

I asked Ihor how he finds reward amidst such a grueling sport, in which the training and competition are often solitary. He answered that his true reward is the experience of overcoming challenges. I think by this he means personal barriers, like those you encounter in your own body and mind while doing something incredibly difficult like running an ultra.

Then he said something fleeting but compelling: “you’re never the same person at the end of the race as when you started.” To me this conveys a sense of ‘becoming,’ that through the challenges we overcome, and the suffering we endure during our ordeal, we change and, importantly, grow. I find it fascinating to see how Ihor regards the pain and suffering inherent in his sport not as depleting, but as a way to ‘become’ something and someone better, to grow further. Perhaps all of us can strive to reframe the challenge, pain, and suffering we face in our work and lives, into a beautiful growth opportunity, the way Ihor does.

He also conveyed that overcoming challenges creates 'meaningfulness' for him. I didn’t press him to elaborate, but my interpretation was that pursuing these brutally difficult goals, including the suffering they entailed, represented a deep experiential feeling confirming he was squeezing the most out of his life. It seemed he was saying that the suffering, and the gratification of overcoming it, improved his life: it rewarded him, helped him grow and ‘become’ stronger, or revealed a strength of will he could carry into other domains of life.

So the lesson for me here is that the suffering involved in pursuing and achieving a challenging goal isn't just cold, uncomfortable, indifferent and inert. Perceived another way, it can be a source of joy, growth, and significant personal meaning and enrichment.

Go beyond mere motivation

This point is also a bit Zen-like, like the last one. Ihor spoke briefly about the difference between motivation and obsession. He said motivation is unreliable, and inferior. If it’s too cold outside, or raining, you may feel unmotivated to train. However, if you are obsessed, you will train regardless of how you feel, and you will tap into a deeper reserve of energy.

I interpreted his comments as saying, motivation is fallible, optional, a condition in which you still have choice to say “I don’t want to do that.” But obsession implies there’s no choice but to be motivated. It suggests you’re so committed that the window for choosing a different course of action is closed. It’s an energetic force that’s locked-in and unwavering.

Also, maybe obsession represents a kind of force that is more of an identity than a transient experience. Perhaps in this state, you’re not just pursuing a goal, you ARE the goal. The goal defines who you are and how you want to be in the world, and not pursuing it would feel akin to stripping yourself of the essence of your being.

That’s a serious level of commitment, and maybe the kind of energy that’s needed to reach your own personal limit of performance.

(When John first told me about Ihor, he said “underneath his sunny disposition, there is a ruthlessness to his motivation that you don’t see in many Canadian athletes.” He was gushing with admiration as he said this.)

The role of ‘fun’ when pursuing difficult goals

What’s the role of ‘fun’ in seeking high-performance? This sounds like a silly question, but for Ihor fun is crucial in fueling his energy and drive. Other ultra-marathoners promote a serious, and workman-like attitude, but he chooses to see his races as a ‘celebration or festival of fitness.’ He finds fun in the beauty of the outdoors, and relishes racing in isolated, untouched terrain that humans can only reach by foot. (It’s interesting that his light mindset stands in contrast with the seriousness of the names of ultra-marathon races… the Sinister Seven, The Canadian Death Race, etc.)

This reminded me of an interview I once watched of a New Zealand All Blacks rugby player. He said “yeah the coach just told me to go out and express myself.” Express yourself. To do that while playing under significant pressure, in front of thousands of fans, while challenging yourself to the limit – that sounds like a mindset that renders a tense situation into one that’s more fun and motivating. A beautiful thought.

I also thought back to my former coach John, who told me that when he holds high-performance athlete development camps, he measures something called the ‘stoke factor’ afterwards. This is a measure of how much fun athletes had at the camp, and he sees it as an important proxy for motivation and commitment.

So though it sounds trivial, Ihor reminds us that even when you’re pursuing hard goals, ‘fun’ is a vital source of energy and drive.

Community promotes high-performance

Ihor suggested that sharing suffering with others within a community, makes it more tolerable. He says there’s something reassuring about racing with a large group of people, who you know are all feeling the same pain as you. There’s a collective experience happening in that moment, a shared camaraderie, that becomes a source of strength.

“We are racing yesterday’s self”

At one point in the interview, when describing the mindset he brings to his sport, Ihor said “at the end of the day, we are racing yesterday’s self.” I thought this was profound. It provoked in me the thought that when we set goals, we may consciously or unconsciously phrase them in reference to others. In Canadian culture, which is individualistic, this may be reflexive, since we place a great deal of importance on winning, which we usually define as the zero-sum vanquishing of our competitor. But if reaching our potential, growing and improving are our goals, we can only measure these using a personal reference point. We never say "we strive to reach our potential relative to other people." No, potential is a personal, self-directed concept, and doesn't involve winning or competition with others. This line of thinking made me wonder if this mindset of self-competition, focusing on reaching one's potential, is a valuable framing when striving to reach very demanding goals, and might be more energizing on a long journey than dwelling on beating others.

Rethinking failure

At the end of our conversation, I asked Ihor what final advice he’d share with others who are pursuing hard goals. He told me a story about how he was considering entering a certain type of race – called a backyard ultra, the kind with the repeating loops – and wasn’t sure he wanted to do it. His girlfriend (now fiancée) told him at the time “what’s the worst that can happen?” He went on to achieve incredible success in that format over many races. (The other lesson here is Ihor is marrying a wise woman.)

This reminded me of the well-established psychological finding that we as humans are loss averse – we feel the pain of losses more deeply than we feel the joys of winning. In a nutshell we’re afraid to fail, and we may overestimate the risk of failing.

It also reminded me of a story told by the musician Jeff Tweedy, who said that he sometimes intentionally tries to write bad songs, to fail on purpose, even though he thinks he won’t like the end product, just to 'unstick' his creative process. To him, failure is an important signpost on the path to progress, something to be approached on the way to generating a valuable creative output.

Ihor’s message, too, I think, is that we can change the way we think about failure (just as he alters the way he thinks about pain during a race) and can summon the effort to at least try to take one more imperfect step forward, and then another, and then another… until we find we've done something we've never done before.

Ihor's contact information

Ihor is available for corporate speaking engagements. If interested, please connect with him using the following information.

Email: verysihor@gmail.com

Instagram: ihorverys

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/goshafromlviv

Appendix

While we’re on the topic of goal setting, this article mentioned another technique I found interesting, called ‘layering.’ Instead of locking into one goal, consider setting a dream goal, and silver goal, and a bare minimum goal.

If you’re interested in reading an incredible story of human resilience, try 'The Wager' by David Grann. If you’re like me, after reading it you’ll realize that whatever suffering you’re experiencing, you can endure much much more (like the poor sailors mentioned in the book did).

Tim Jackson, Ph.D. provides advisory and deep expertise on executive leadership development, to dynamic and high-performance organizations.

Tim's services include in-depth executive assessment for development; one-on-one executive advisory rooted in his deep expertise of the drivers of leadership effectiveness; workshops on a variety of leadership topics built with evidence-based data; and facilitated sessions that create dialogue among senior leaders on important leadership themes, in an environment that promotes shared learning.

Throughout his 18-year career, Tim has worked with a wide variety of clients, including CEOs, executives, managers, and individual contributors; leaders located in Canada, the US, Europe, and China; individuals spanning 11 different industry sectors and every key functional area; and those driving major change inside private-equity owned businesses.

Tim has published his ideas about leadership in various outlets, including The Globe and Mail, Forbes.com, several HR trade magazines, and peer-reviewed journals. He also writes original articles about leadership topics in his newsletter at www.timjacksonphd.com. He has also shared details about his practice at leading conferences like the Society for Industrial and Organizational Psychology.

Tim has a Ph.D. in Industrial/Organizational Psychology from Western University, where he explored the drivers of leadership effectiveness in both his Master’s and Dissertation-level research. He and his family are based in Toronto, ON.

Please feel free to contact Tim with your feedback about this site, questions about his services, or to share your own ideas about leadership in organizations.

Email: tjackson@jacksonleadership.com

Phone: 647-969-8907

Website: www.jacksonleadership.com

Newsletter: www.timjacksonphd.com

Member discussion