An occupational hazard for executives: Financialization

About six months ago I read a book written by a well-known former faculty member at MIT’s business school, Edgar Schein, called Organizational Culture and Leadership.

I had wanted to read the book for about 20 years. I can remember, when I interviewed with my soon-to-be graduate school advisor, I told him I planned to read it (though I didn’t). A few years ago, I finally purchased a copy – the 5th edition (published in 2017). Then not long after that, my Father passed away, and I inherited many of the books from his library (or at least the ones I wanted to hold onto). In his collection was a pristine 1st edition copy of the book (published in 1985). Now I found myself with two versions of the same book I’d been wanting to read for over 20 years. It was time to finally read the damn book.

I started combing through the pages for ideas about how organizational culture works. At the time I was writing a newsletter article on how culture influences leadership. I wrote my dissertation in part on this topic, but focused mostly on the impact of societal culture on leadership. Schein helped me understand what culture looked like inside the four walls of a company.

One thing I really like about Schein is he preferred qualitative research. As one story goes when he left grad school, his first job was with the military, where he interviewed former prisoners of war. Through those experiences, he developed clear views about how organizations and their cultures, can hold their employees captive in a sense, and over time and in subtle ways, shape their attitudes and worldviews (often unconsciously). From this experience, he went on to embrace qualitative methods (e.g., interviews, observations) throughout his career. As I’ve progressed as a professional, my work has also become more qualitative and interview-based, so I resonate with Schein in this area.

Another reason I like Schein is he spent most of his career wearing two hats, one as a professor, the other as a consultant. He often worked so closely with his clients, that he became a kind of embedded quasi-employee, learning so much through his work and observations, that he later wrote books about some of his most long term clients (a company named DEC, and the Singapore Economic Development Board). I like his bent towards ‘application’ and ‘the field’ since much research on leadership, at least in the psychology discipline which I grew up in, can be abstract and difficult to apply with executives.

So I was working my way through Schein’s book, having a great old time, feeling good about myself that I was finally reading it, when I came across a passage in one of the last chapters that almost made me fall off my chair.

The passage comes from a section which describes three main professional subcultures within most organizations: operators, designers, and executives. Operators are those who are close to ‘the line,’ the kind of people that feel like they run the place. They don’t work in sales or marketing, and they don’t ‘design’ the place the way engineers do. Engineers or designers set up and guide the use of machines and technologies in a company. They also hold the knowledge about how that technology should be implemented.

And then there’s the executive subculture. In Schein’s definition, executives represent the CEO and the top executive team reporting into them. The description of this subculture is what made me stop and almost drop the book. Here I’d like to quote directly and at length from this section, so you can read it for yourself. I've also italicized parts that seemed particularly noteworthy to me:

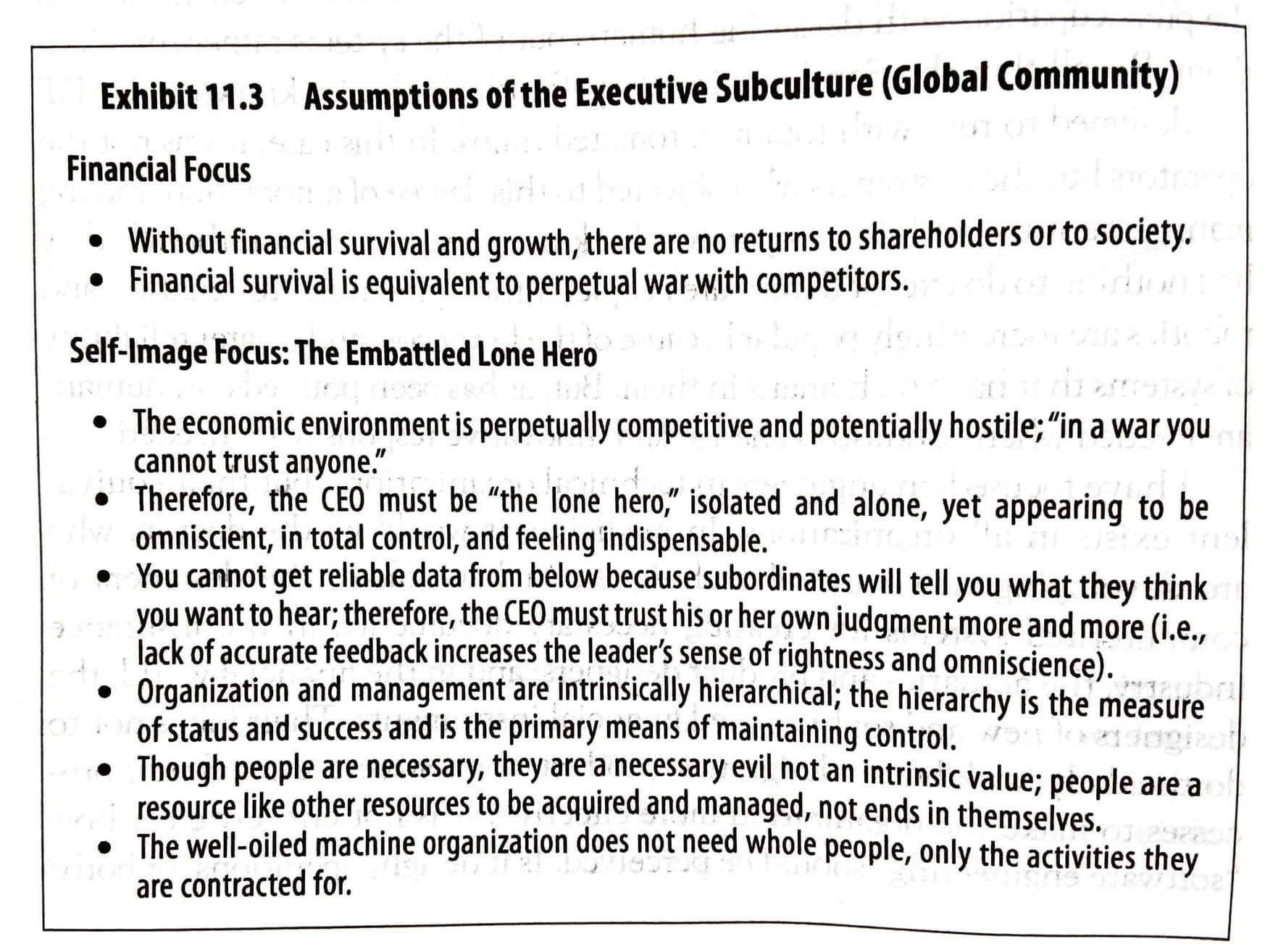

“A third generic subculture that exists in all organizations is the executive subculture based on the fact that top managers in all organizations share a similar environment and similar concerns. This subculture is usually represented by just the CEO and his or her executive team. The executive worldview is built around the necessity to maintain the survival and financial health of the organization; it is fed by the preoccupations of boards, of investors, and of the capital markets. Whatever other preoccupations executives may have, they cannot get away from having to worry about and manage the financial issues of the survival and growth of their organization (italics mine). In private enterprises, the executives have to worry specifically about profits and return on investments, but financial issues around survival and growth are just as salient in the public and nonprofit enterprise. The essence of this executive subculture is described in Exhibit 11.3…"

"...For example, the executive level has been shown in a study by Donaldson and Lorsch (1983) to make all decisions through a “dominant belief system” that translated all the needs of their major constituencies – the capital markets from which they must borrow, the labor markets from which they must obtain their employees, the suppliers, and, most important, the customers – into financial terms (italics mine). Executives had complex equations by which they made their decisions. There was clearly an executive culture that revolved around finance (italics mine)…

The basic assumptions of the executive subculture apply particularly to CEOs who have risen through the ranks and have been promoted to their jobs. Founders of organizations or family members who have been appointed to these levels exhibit different kinds of assumptions and often can maintain a broader, more humanistic focus (Schein, 1983). The promoted CEO tends to adopt the exclusively financial point of view because of the nature of the executive career (italics mine). As managers rise higher and higher in the hierarchy, as their level of responsibility and accountability grows, they have to become more preoccupied with financial matters and they also discover that it becomes harder and harder to observe and influence the basic work of the organization. They discover that they have to manage at a distance, and that discovery inevitably forces them to think in terms of control systems and routines, which become increasingly impersonal.

Because accountability is always centralized and flows to the tops of organizations, executives feel an increasing need to know what is going on while recognizing that it is harder and harder to get reliable information. That need for information and control drives them to develop elaborate information systems alongside the control systems and to feel increasingly alone in their position atop the hierarchy.

Paradoxically, throughout their career, managers have to deal with people and surely recognize intellectually that it is people who ultimately make the organization run. First-line supervisors, especially, know very well how dependent they are on people. However, as managers rise in the hierarchy, two factors cause them to become more “impersonal.”

First, they become increasingly aware that they are no longer managing operators but other managers who think like they do, thus making it not only possible but likely that their thought patterns and worldview will increasingly diverge from the worldview of the operators. Second, as they rise, the units they manage grow larger and larger until it becomes impossible to know everyone personally who works for them. At some point, they recognize that they cannot manage all the people directly and therefore have to develop systems, routines, and rules to manage “the organization.” People increasingly come to be viewed as “human resources” and are treated as a cost rather than a capital investment (italics mine). The immediate subordinates also pose a problem in that they are people, but they are competing for the CEO’s job and therefore have to be treated impersonally to avoid accusations of favoritism.

The executive subculture thus has in common with the engineering subculture a predilection to see people as impersonal resources that generate problems rather than solutions. Another way to put this point is to note that in both the executive and engineering subcultures, people and relationships are viewed as means to the end of efficiency and productivity, not as ends in themselves.”

(p. 226-228, 5th edition)

Why was this section so striking to me? I think it’s because of how negatively Schein portrayed members of the executive ranks. His description took me back to 2003, when a professor of law at the University of British Columbia wrote a bestselling book called ‘The Corporation’ in which he argued that if a company was diagnosed by a clinical psychologist, it would be classified as a sociopath (the book was later adapted into a popular film). At first glance, it seems like Schein is describing CEOs and senior leaders as sociopaths.

However, after further reflection, I realized Schein isn't criticizing executives as immoral. Rather he’s describing several forces, biases, or ‘gravitational pulls’ that executives feel in their roles. These are impersonal forces that might condition people to think and act in certain ways, because of how their role is structured, and the incentives they experience. In psychology, we sometimes call these ‘strong situations.’

This is my interpretation of Schein’s key points:

1. First, executives feel a pull towards financializing everything and everyone.

2. Second, this emerges in part due to the fact that their job, their responsibility, in fact their DUTY, is to manage the finances of the company. In a sense, they are being paid to financialize everything and everyone. That’s the yardstick against which their performance is measured. And that’s not their fault.

3. Third, this financialization emerges in part because executives are quite distant from the people (and the processes) they manage. As a result, people become more of an abstraction to them.

4. Fourth, due to their perch on top of the hierarchy, and the political dynamics surrounding them, they are highly isolated. This might contribute to them being suspicious of others (like of direct reports who want their job), and of the information they receive. This isolation might contribute to creating robust and impersonal control systems to manage information and people, which further alienates them from others.

5. Fifth, CEOs feel tremendous pressure to show they are in total control, omniscient, and indispensable. They need to manage impressions so that they constantly elicit the confidence of others. Perpetuating others’ ongoing belief in their success is a primary way that they preserve their influence and followership. Perhaps this interferes with establishing authentic relationships and connection.

After reflecting on these points further, I felt a great deal of compassion for CEOs and senior executives who swim in this subculture, because it sounds like a brutally difficult job.

But I think a key point is this… These forces, and the financialization of people inherent in them, represent biases of the role that can suck executives into a style of being or acting, without them knowing it. And yet, if you’ve worked in corporate settings for any length of time, you’ve encountered CEOs who are incredibly humane, moral, and kind. So executive subculture, and the extreme financialization of people is not destiny. It’s not chiseled on stone tablets at the top of Mt. Sinai. Executives can choose a different path, they can resist the gravitational pull, and many do. However, it is important to remember that working in these environments may weaken executives’ ability to perceive people and relationships in typical ways. At the very least, it seems wise to cultivate a keen awareness of these forces, and perhaps to resist them where possible.

Music

Tim Jackson, Ph.D. provides advisory and deep expertise on executive leadership development, to dynamic and high-performance organizations.

Tim's services include in-depth executive assessment for development; one-on-one executive advisory rooted in his deep expertise of the drivers of leadership effectiveness; workshops on a variety of leadership topics built with evidence-based data; and facilitated sessions that create dialogue among senior leaders on important leadership themes, in an environment that promotes shared learning.

Throughout his 18-year career, Tim has worked with a wide variety of clients, including CEOs, executives, managers, and individual contributors; leaders located in Canada, the US, Europe, and China; individuals spanning 11 different industry sectors and every key functional area; and those driving major change inside private-equity owned businesses.

Tim has published his ideas about leadership in various outlets, including The Globe and Mail, Forbes.com, several HR trade magazines, and peer-reviewed journals. He also writes original articles about leadership topics in his newsletter at www.timjacksonphd.com. He has also shared details about his practice at leading conferences like the Society for Industrial and Organizational Psychology.

Tim has a Ph.D. in Industrial/Organizational Psychology from Western University, where he explored the drivers of leadership effectiveness in both his Master’s and Dissertation-level research. He and his family are based in Toronto, ON.

Please feel free to contact Tim with your feedback about this site, questions about his services, or to share your own ideas about leadership in organizations.

Email: tjackson@jacksonleadership.com

Phone: 647-969-8907

Website: www.jacksonleadership.com

Newsletter: www.timjacksonphd.com

Member discussion