How CEOs can detect and address underperformance in their leaders

Introduction

In May a freelance journalist working for The Globe & Mail (one of Canada’s national newspapers) reached out to ask if I’d answer some questions about leadership.

I spoke with her for over an hour, responding to questions she sent me in advance, and which I prepared answers for.

The Globe published the article in early June, but due to space constraints the journalist included just a few short quotes from our lengthy discussion.

In this article I’m sharing my full-length responses in case they’re helpful to readers.

The following were the questions she asked me, and which I answer below:

- As a CEO how do you find out how effective a leader is?

- What are some red flags top executives need to be aware of to judge their leaders?

- What do you do if the leader isn't effective?

As a CEO how do you find out how effective a leader is?

The following are several data sources CEOs could use to determine the effectiveness of a leader underneath them.

A key takeaway here is that no one data point is sufficient, and CEOs should triangulate in on a determination about an executive’s effectiveness using multiple methods and data sources.

- Business-relevant metrics linked to team functioning: CEOs might start by reviewing metrics indicating how the leader delivers business-relevant performance through their team, like P&L, sales, revenue, output, or safety - whatever relates most to their role and is also valued by the business. They should involve coordinating other people to deliver results, not just the leader themselves performing well (e.g., giving a competent presentation to the Board). A limitation of these metrics is they don't directly measure leader behaviour, and can be contaminated by other influences (e.g., if the market is down, a good leader can appear ineffective based on their team’s performance metrics – something I described in the evocative opening scene from this previous article). Another problem is some jobs lend themselves to measurement using clear-cut criteria (e.g., sales), but others less so.

- Talent review discussions: At many companies, senior executives meet once per year to discuss and assign performance ratings to more junior executives. These meetings are helpful because they surface and aggregate multiple perspectives about leader performance. Executives can also question and challenge each other, which may provoke deeper analysis. At the same time a limitation is this format can slide into subjective, impressionistic, ‘vibes’-ladden commentary about a leader, which may not be rooted in direct observation or experience. Also the loudest or most emotional viewpoint might receive more weighting, which may bias the final evaluation.

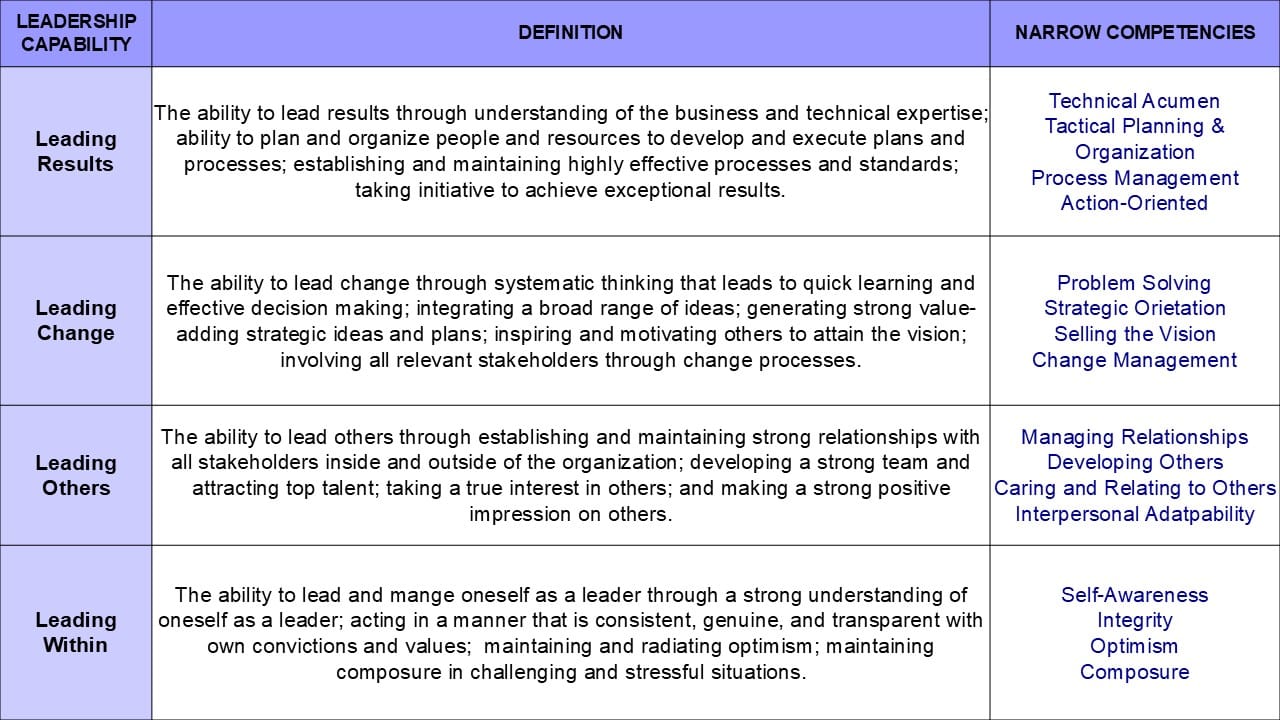

- Competency-based assessments: CEOs can also use competencies as a ‘scorecard’ for judging leadership effectiveness. A competency framework is a list of behaviours the company endorses as contributing to leader effectiveness, and which align with their idealized culture. Many large firms create their own competency models, which they use as reference points or checklists during talent discussions, one-on-one performance reviews, or development conversations. Typical leader competencies include skillsets like leading change, strategic thinking, managing relationships, planning and organizing, among others. Competency-based evaluations are useful because they encourage rating the leader’s behaviour, and are less contaminated by factors outside the leader's control (e.g., the market). Another advantage is competencies represent a comprehensive checklist, and force the rater to evaluate a wide range of behaviours, not just those that come to mind.

- Engagement surveys: Engagement surveys measure many aspects of the employee experience, like job satisfaction, commitment to the company, and a sense of belonging at work. In addition, they are a sneaky way to measure leadership. They aren’t primarily measures of leadership effectiveness (though they include some questions about satisfaction with supervisors) but if you aggregate results within a team or function, you get a sense of how happy team members are within that group. Based on that you can make educated guesses about leadership performance – i.e., if team members feel 'engaged' it's likely their leader is effective. A limitation of using engagement surveys this way is they don’t explain ‘why’ a leader is performing well or not. The surveys produce summarized numerical or percentile data which can’t offer causal explanations. And the open-ended comments written by respondents may be cryptic, or poorly worded, adding little clarity. But engagement surveys can be used as a macro-level indicator of leadership effectiveness, and as a starting point for asking questions to team members about what’s driving the findings.

- Assessment centres: Assessment centres (ACs) are batteries of multiple tools, simulations, and exercises designed to measure leadership effectiveness, administered and scored by multiple raters. Think "multiple methods, multiple raters." They can involve aptitude/intelligence tests, personality measures, and various types of simulations (some solo, and some group-based involving actors, other executives, or fellow AC participants). They can last anywhere from a half day, to multiple days. ACs create an artificial context, but despite this pretense, if executed and scored well they produce comprehensive and high-quality data about leader effectiveness. A limitation is ACs are often expensive and time consuming to administer. They also require considerable expertise to plan and execute. However if CEOs can access recent AC data about a leader –e.g., gathered during a high potential development program, or an assessment conducted prior to selection or promotion - it provides valuable clues about their effectiveness.

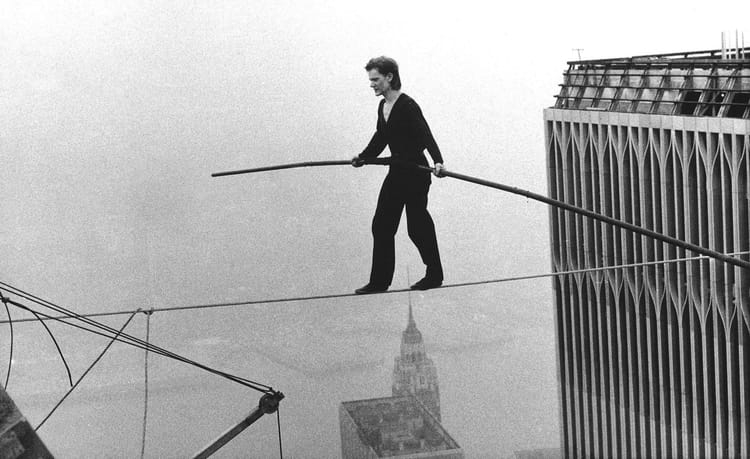

- 'Fish out of water' and other stretch assignments: One stretch assignment CEOs might use to evaluate a leader's effectiveness is the 'fish out of water' format. Here a leader is asked to guide a function they’re unfamiliar with: a sales person leads marketing; a marketer leads R&D; an HR specialist leads a manufacturing facility. This is often a rite of passage for executives in large companies. The rationale is to strip out a leader’s technical expertise, and ask, absent that, ‘can they succeed if they only rely on their leadership skills, without any technical knowledge to save them?’ Other stretch assignments CEOs might design include moving to a new geography/culture, managing a major organizational change, or resurrecting a failed business. Each of these provides a different stress test of a leader’s abilities, and 'reveals' unique underlying skills. A downside of these assignments is they require time and energy to set up, and patience before you can judge a leader’s effectiveness. Another limitation is that you can argue these stretch assignments should be developmental, not evaluative. After all, while people are learning, their performance may suffer and they may appear ineffective for a time. But maybe that’s ok. Perhaps they’ll eventually grow a more diversified and robust leadership skill set due to the experience, and maybe that should be the point.

What are some red flags top executives need to be aware of to judge their leaders?

Objective measures

- Chronic underperformance on key metrics: As mentioned, these could include P&L, revenue, safety, or any objective metrics related to the leader's role. But again, CEOs should use this in combination with other data points, and with an understanding of what’s happening in the broader context (e.g., team, organization, and market).

- ‘Undesirable’ turnover: If a leader is losing low performers, that might be healthy for the business, and a sign that they’re challenging the team in constructive ways. However, if they’re losing multiple skilled, high performing team members, that is maladaptive for the organization and a sign of poor leadership.

- Low engagement scores: As mentioned above, if a leader’s team members are chronically unhappy based on engagement survey results, and relative to the other functions, or other segments of the company, that could be a sign of ineffective leadership.

Behavioural

These themes reflect my own idiosyncratic knowledge, philosophy, and views about what derails executives, based on my career researching and working with leaders. Others may prefer to focus on different markers, but these are ones I tend to key in on.

- Avoidance/passivity: I think one of the most dysfunctional leadership profiles is simple avoidance and passivity. Benign neglect may not seem harmful, but it is, and since it's subtle, it often goes unnoticed. If the roof is on fire, and there’s an emergency that needs attention, the leader needs to guide a response. If they’re unavailable – even if they have a good excuse, like being busy or traveling – people really dislike it. Leaders don’t have to micromanage, but they must be available and responsive when needed. Also minimal oversight of a team can allow bad actors to display poisonous behaviours that spread cultural damage through the broader organization.

- Hostility: In the last 20 years researchers have made considerable progress studying incivility and abuse in the workplace, including acts perpetrated by leaders. These behaviours can include sustained verbal or non verbal hostility, bullying, coercion, ostracism/silent treatment, public criticism or ridicule, lack of praise, threats, intimidation, etc. Apart from the directly demoralizing effects of this treatment, team members can also mimic the leader’s hostility, which can (again) spread throughout the company.

- Too self-centered and not prioritizing the collective: Having a collective orientation is vital for leaders. If the leader pursues goals only to aggrandize themselves and not to generate any collective benefits, if they see themselves as separate from the team (“you guys work on that over there, I don’t need to be involved”), or if they don’t give and share credit with the team, all of these can be demotivating.

- Dehumanizing: This involves treating people as cogs inside the machine of capitalism, with no regard for their personal needs, or the importance of showing consideration or respect. frankly the higher a leader climbs in the hierarchy, the easier it is to fall into this pattern - call it an occupational hazard of being an executive.

- Dark triad: There are three personality traits – collectively and ominously called the ‘Dark triad’ - which seem to wreak havoc with people’s workplace experience, though there is still mixed research on how they impact leadership performance (believe it or not). If I had to guess, in the long-term, they probably degrade leadership effectiveness, since they all involve selfishness and manipulativeness. (I certainly wouldn’t want to work for one of these leaders.) Based on what I know, if I was running a company, I’d be vigilant about whether any of my leaders display extreme levels of these. Here are the Dark Triad traits ... Sociopathy involves dehumanizing others, treating people as vehicles for personal gain, callousness, and a lack of empathy or remorse. Machiavellianism involves being manipulative and demonstrating amorality. Finally Narcissism involves grandiosity and pride, high ego, lack of empathy, and usually some underlying and brittle insecurity.

- Wide discrepancy between stated and practiced culture: If the leader says they value transparency, but meanwhile hoard information, that’s disorienting. If they say they want to foster a culture of empowerment, yet they micromanage, again this is confusing. Enormous gaps between what leaders say and do leads to junior staff spending inordinate amounts of time trying to decode and predict the underlying motivations and priorities of the leader. What do they really mean? What do they really want? All of this is wasted energy, which could be better directed towards achieving meaningful goals. In addition, team members interpret the inconsistency between words and actions as a marker of unreliability, which can erode the leader’s credibility.

- Emotionally erratic: On rare occasions emotional outbursts from the leader can be useful in signaling their priorities. “Wake up everyone, this is what’s important!” This kind of emotion clarifies and aligns others to valued goals, amidst the noise of lesser minutia. However, with norms in the workplace evolving towards greater civility, I would guess most people interpret outbursts of negative emotion as threatening and demotivating.

- Interpersonal or relationship difficulties: Leadership, especially at executive levels, is an interpersonally demanding job. If leaders have trouble building and maintaining trusting relationships, that’s a major problem. Also an inability to build relationships can leave leaders isolated, either with a weak network to tap for advice, or without a coalition at the company that can protect or advocate for them (making them more vulnerable).

- Rigidity: There are many faces of rigidity, all of which can interfere with leaders adapting to their environment. It can manifest as being unable to change your mind (i.e., getting stuck on an idea), being unable to change your behaviour despite evidence you should, or stifling dialogue by interrupting, not listening, dismissing, or avoiding interactions because you don’t want to hear countervailing perspectives. It can also contribute to overcontrolling behaviours, narrow thinking, and an inability to take the perspective of other people.

- Tribalism leading to internal competition: Tension due to competing interests across functions is normal. In fact some functions are meant to act as checks and balances against others (finance anyone?). And competition directed towards market competitors is always welcome. However, if too much competitive juice gets directed at other leaders or functions inside the company, to the point where it leads to disparaging, excluding, or highly political behaviour, this can lead to self-injurious internecine civil war within the company.

- Lack of self awareness: This involves the inability to observe and reflect on your own thoughts/feelings, to see perceive the impact of your behaviour on others, to theorize what others might be thinking, or to consider how you might be viewed by others. These deficits limit flexibility and adaptability, and learning from social cues.

What do you do if the leader isn't effective?

A key message here is that the most effective intervention is the CEO's direct involvement in addressing the situation, and that this requires considerable self-assessment, due diligence, and preparation.

Data gathering…

- Self-assessment: If you’re a CEO, and the underperforming leader is your direct report, it’s important to scrutinize your own performance as a leader first. Ruling out the possibility that you've contributed to their underperformance will help you maintain credibility if you need to hold an accountability conversation. Reflect on whether you’ve created the right conditions for this person to succeed. Have you set and communicated clear goals and expectations, provided sufficient resources, removed roadblocks (sometimes called instrumental leadership), made yourself available to act as a sounding board, and created a culture that supports transparent yet respectful communication?

- Due diligence: Due diligence goes beyond self-assessment to gather more in-depth data. It deepens your understanding of possible causes of underperformance, counteracts ingrained biases about what's underlying the decrement, and prepares you to discuss the situation with the leader. So pretend you're an investigative journalist: speak to the leader, speak to the leader’s coworkers, speak to HR, speak to your trusted advisors (i.e., other senior executives in the company). Consult all the available data (as mentioned, based on key performance metrics, talent reviews, competency-based evaluations, engagement surveys, AC data, and anything else you can find). Triangulate in on a sense of how they’re performing. Doing this due diligence is important because we have default wiring as human beings to attribute fault and blame to individuals (it’s called the fundamental attribution error), and to ignore complex and/or situational factors driving underperformance. Due diligence pushes back against that bias.

- Consider multiple explanations: Once you’ve conducted your due diligence, formulate as many explanations as possible for the leader’s underperformance, and consider the plausibility of each. This is important because it loosens up your thinking, renders it more flexible, and prepares you to ask thoughtful and searching questions to uncover root causes. (This is like doing a warm up or mobility routine before an exercise workout - it prepares you for a more productive session.) Deep and flexible thinking is your friend here; shallow thinking and getting stuck on your preliminary assumptions is your enemy. If the person was a great performer for 10 years, then started to underperform, what’s causing this? Health issues? A highly stressful context (like Covid, or another crisis)? A changing business environment that necessitates learning new skills? Do they have a skill gap, and need training? Are they misfit into their role? Generate as many explanations as possible.

Possible interventions…

- Series of meetings with the leader: Once all the prep is complete, the CEO needs to start the intervention. This usually involves a several meetings following a structure like this one…

- Exploratory discussion: Ask the leader for their assessment of the situation. Share your ideas about what's going on, including any rationale. Ask the leader what they think about your ideas and the rationale. Ask if you've missed anything that might help you understand what’s happening. Discuss factors both outside the leader's control, and within their control that might have influenced their performance. Ask what support or solutions might be most helpful to the leader.

- Communicate the standard: Articulate in clear terms the precise performance standards you expect. Make goals and expectations crystal clear. Explicitly state the need for an improvement in performance. Be careful not to jump to this step before finishing your due diligence and the exploratory discussion.

- Establish an improvement plan: Agree on what the leader will do to enact change, and gain commitment on following through. If you're suggesting other interventions (e.g., training, remedial coaching - see below), discuss those and include them in the plan.

- Establish a recurring meeting cadence: Schedule follow up meetings to check in on progress, offer advice and support towards improvement, and (if needed) reiterate the standard you expect. These meetings are vital because they signal you prioritize this issue, which will cause the leader to do the same.

- Get involved: As mentioned in the 'self-assessment' section above, provide direct instrumental assistance as needed. Offer resources, provide feedback, act as a sounding board, give advice, and remove road-blocks where possible.

- Training: If the leader lacks an important skill, consider asking them to complete additional training. Explore programs internal to the company. On the external side, business schools offer a wide range of open enrollment training courses, many of them in virtual or even self-paced formats. Many of these programs work well for narrowly defined skills, like communication, presentation giving, or negotiation. But even for complex skills like leadership, more knowledge can't hurt, and some of the training is likely to transfer back to the job. To me this is a low risk option, with more upside than downside.

- Remedial coaching: This involves matching the leader with an advisor or external consultant who collects assessment and feedback data (often 360 surveys) that examine in greater detail the problematic behaviours interfering with the leader's effectiveness. In my experience, leaders who start to derail either a) aren’t aware of their maladaptive tendencies, and/or b) have developed sophisticated mental processes for discounting or defending against information that challenges the notion they’re effective. Advisors will help these leaders perceive and understand their counterproductive tendencies, in a compassionate way. Once that uncomfortable but essential process concludes, advisors help the leader set goals for improving, and offers advice/support on how to accelerate change. Note that this process only works if the CEO is involved (e.g., supporting the process, reviewing the goals, meeting to discuss goal progress). Their involvement legitimizes the program, and compels the participant to spend time on it.

- Networking solutions: This involves connecting the leader with other sources of social and mentoring support, which may help them build their skills. In practice this could mean matching the leader with a senior-level mentor, or a retired executive, who was successful in their role in the past. The match could be with another leader at the same level who is more skilled in the areas where the leader needs to improve. HR leaders can sometimes provide ‘internal’ coaching and support. Another form of social and mentoring support can come from networking groups which create confidential forums for sharing challenges and asking for advice from other leaders. Some examples include executive roundtables, women in leadership programs, or a format like Young President’s Organization.

Music

Here jazz pianist Fred Hersch starts off mirroring the song structure "Witchita Lineman," then takes a meandering jaunt, and then returns to the original melody in the final moments.

Tim Jackson, Ph.D. provides advisory and deep expertise on executive leadership development, to dynamic and high performance organizations.

Tim's services include in-depth executive assessment for development; executive advisory and coaching rooted in his deep expertise of the drivers of leadership effectiveness; workshops on a variety of leadership topics built with evidence-based data; and facilitated sessions that create dialogue among senior leaders on important leadership themes, in an environment that promotes shared learning.

Throughout his 18-year career, Tim has worked with a wide variety of clients, including CEOs, executives, managers, and individual contributors; leaders located in Canada, the US, Europe, and China; individuals spanning 11 different industry sectors and every key functional area; and those driving major change inside private-equity owned businesses.

The following are examples of how Tim has delivered value to his clients: he assessed and coached 28 leaders in a large Canadian CPG company over a 5 year period, including preparing high potentials for promotion and helping derailing leaders course correct; he coached senior leadership team members and middle managers in a global chemical company to navigate dynamic change resulting from the largest acquisition in their history; and he provided assessment, coaching and advisory support to the CEO of a Canadian ‘supercluster,’ a federally-funded accelerator of strategic economic activity (this cluster received renewed funding in early 2023).

Tim has published his ideas about leadership in various outlets, including The Globe and Mail, Forbes.com, several HR trade magazines, and peer-reviewed journals. He also writes original articles about leadership topics in his newsletter at www.timjacksonphd.com. He has also shared details about his practice at leading conferences like the Society for Industrial and Organizational Psychology.

Tim has a Ph.D. in Industrial/Organizational Psychology from Western University, where he explored the drivers of leadership effectiveness in both his Master’s and Dissertation-level research. He and his family are based in Toronto, ON.

Please feel free to contact Tim with your feedback about this site, questions about his services, or to share your own ideas about leadership in organizations.

Email: tjackson@jacksonleadership.com

Phone: 647-969-8907

Website: www.jacksonleadership.com

Newsletter: www.timjacksonphd.com

Member discussion