Stretch goals: Panacea, paradox, or poison?

Panacea

Jack Welch was the Chairman and CEO of General Electric from 1980-2001. In the first half of his tenure, he oversaw the leaning out of the company, as they exited about 118K people, and cut out businesses they couldn’t be ‘number 1 or number 2’ in. His intention was to fix, sell, or close any units that would never be leaders in their market.

After streamlining the company and their talent in the 1980s, starting in the 1990s Welch felt the stage was set to become a truly high performing organization, and he decided to push the business beyond what many perceived as it’s limits.

One idea he used to propel this surge towards high performance was ‘stretch goals.’ (He seems to have been the first to use the term.) In his telling, this involved “using dreams to set business targets, with no real idea of how to get there.” He was tired of the same old budget meetings. Leaders of a business would show up and say they could achieve 10 next year. Management would push them for 20. After hours of PowerPoint slides and pitched negotiations, they would settle at 15. He called it an “enervating exercise in minimalization.” He felt that by talking about stretch targets he could pivot the conversation and its underlying adversarial dynamic towards a focus on what’s truly possible in the business, and how to transcend it’s perceived limits.

So he asked his business leaders to set stretch goals, aspirational targets that seemed on their face impossible. He then created a performance management system around this idea, rewarding leaders for achieving stretch goals, but not punishing them if they were missed. Then in combination, he overlaid on top of those stretch targets other core, budget-based goals which were non-negotiable, and which he demanded managers meet (i.e., if you missed them, it would reflect poorly on you and might limit your career progression).

A talented marketer, Welch repeated his visionary idea and narrative over and over, like a preacher in the pulpit on a Sunday, testifying to the miraculous power of stretch goals:

“We have what we call stretch targets. . . . For example, we spent 105 years in this company and we never had double digit operating margins. We said in 1991 we want 15 and we put it in our annual report. We told everybody. 9.6 or 9.5 was our best. We’ll do 14 in 1994, and prices have been going down in the global market. And we’ll do 15 next year. We never did more than 5 inventory turns and we said we’ll do 10. We had no idea how we would get to 10... The big line I use today is that budgets enervate and stretch energizes. It’s real."

Welch’s view typified the belief that stretch goals were a panacea, a performance-enhancing ‘holy water’ that could cure leaders and companies of their self-imposed limiting beliefs, and mediocrity. Hidden in the tall grass of aspirational language here is the subtle suggestion that we are prisoners of our own conventional and incremental thinking, but that stretch goals can set our businesses free to achieve previously unthinkable success. The dogma of stretch goals as all-powerful also contains a hint of magical thinking you might associate with ‘self improvement’ culture – “if you just believe it, you can achieve it.”

Other organizations, even well before Welch’s tenure, also adopted a belief in the power of stretch goals, with some describing memorable and validating case examples.

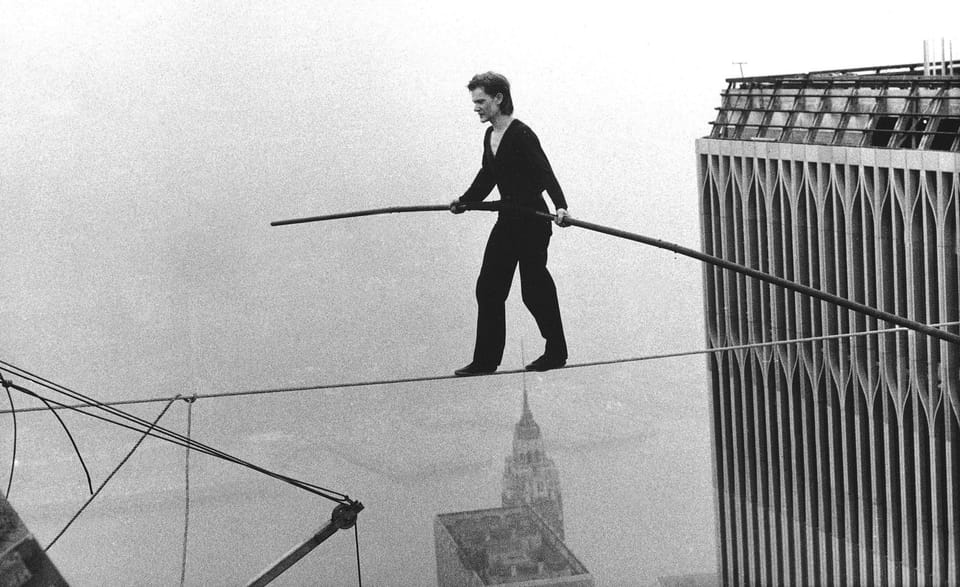

The one I like most emerged back in the early 1970s, at Southwest Airlines. As it goes, on the heels of having to sell off part of their fleet to stabilize their finances, the company set a stretch goal to perform 10-minute turnarounds at gates. Just think about that. That means that from the time an inbound plane arrived at a gate, until it left as an outbound flight with an entirely new set of crew, passengers, and cargo, only ten minutes would pass on the clock. You can imagine employees felt this goal was impossible. However, according to the story, it sparked a search for radically different processes. Eventually, the company borrowed techniques from professional auto racing pit crews, imported them into the commercial airline industry for the first time, and reached their target. The turns were so fast that sometimes the plane would push back from the gate before all the passengers were seated, something you could do in the 1970s before safety regulations later closed that loophole. (See the link below for further details on this story.)

In another success story about the power of stretch goals, Toyota’s seemingly impossible goal of 100 percent near term improvement in fuel efficiency is said to have played a key role in developing its hybrid engine technology. Other companies in the 1990s like Motorola, 3M, CSX, and Union Pacific also went on record as pursuing and benefiting from stretch goals.

And let’s not forget the tech icons who have constructed a kind of leadership and cultural mythology about the virtues of setting goals that others think are impossible.

In the mid 1980s, engineers for the Macintosh computer said they had reduced the boot up time as much as they possibly could, and could shrink it no further. Steve Jobs then asked “if it would save someone’s life, could you shave 10 seconds off?” Eventually they did. Sounds like a stretch goal.

And then there’s Elon Musk. In Walter Isaacson’s biography of Musk, he described how one of Musk’s favourite sayings is ‘maniacal urgency’ and that he routinely likes to cut a production schedule in half, and then in half again. Also sounds like stretch.

Stretch goals have also been idolized by the consultant community. Remember Jim Collins? He was a former management consultant, Stanford MBA and teacher who wrote a bestselling book in 2001 called ‘Good to Great.’ In it he defined the qualities companies and their leaders needed to outperform the average. In the book he wrote that one of the most important attributes of great companies was that they set “big, hairy, audacious goals.” He also pounded the drum for really bold goals in his book previous to “Good to Great,” also a bestseller, called ‘Built to Last.’

What is a stretch goal?

One definition of stretch goals that I like appears in an article written by Duke University professor Sim Sitkin and some of his colleagues.

They write stretch goals are those that seem to be impossible (i.e., have an unknown or 0% probability of attainment) given current capabilities (i.e., practices, skills, knowledge).

The two characteristics that make stretch goals unique are:

- Extreme difficulty – The goal relates to improving performance in a substantial way, perhaps on a routine or known task. For Southwest Airlines turning around planes at a gate was very familiar. However, the target was set way beyond current perceived performance limits.

- Extreme novelty – This means there are no known paths, templates or playbooks to light a way towards goal attainment. That uncertainty forces an energetic search beyond typical routines, processes or knowledge sets to guide a solution. It also energizes the rapid learning of these new approaches, including how to import them into the current situation. For example, Southwest searched for new knowledge and techniques outside their industry, and eventually imported processes used by auto racing pit crews to bolster performance.

Another important feature of stretch goals, according to Sitkin and company, is that they impose an intentional, internally generated crisis on the organization. They call this an ‘autogenic crisis.’ The purpose of this crisis to mobilize thinking in radical, assumption-breaking ways, and to drive rapid learning. Sometimes crisis arrives at an organization’s doorstep as an external force, imposed by the market or competitors, but in the case of stretch goals, it arises by choice and from within.

Paradox

Sitkin and his team's work was a thorough critique of stretch goals that suggested they may not be as miraculous as advertised.

One key assertion they make is that stretch goals are a paradox: they are only useful for some kinds of companies, and the ones most likely to benefit from them, are least likely to use them.

I’ll try to unpack this statement. First, keep in mind that Sitkin and company suggest that stretch goals can lead to wildly different outcomes – either very positive or very negative - depending on the state of the organization.

If they work well, they create an urgent search for new strategies that propel success. If they fail, they trigger disordered and chaotic thinking and action, leading people to check out (i.e., withdraw) from the goal.

But what drives those different reactions? Sitkin and co. say that there are two big factors: a) a lot of slack resources (e.g., money, people, time, training, technology), and b) a recent history of successful performance. In other words, more slack and more recent success maximizes the positive impact of stretch goals.

And now we come to the paradox. Sitkin and co. also say that the kinds of companies most likely to use stretch goals are the ones that can least afford it. For example, those that are in a downward performance spiral, losing money and experiencing a string of failures, may set stretch goals out of a sense of desperation, making a kind of ‘hail mary’ attempt to avoid organizational death. These are the companies least likely to benefit from stretch.

On the other hand, large successful companies with an embarrassing level of excess resources, may become complacent and conservative because of their success, and shy away from using stretch goals – even though they could afford to take risks by setting these goals.

Poison

We've reviewed how some view stretch goals as a panacea, a magical solution that leads to unbelievable performance. We've also seen another more skeptical perspective on stretch goals, that they may only work well in certain situations. A final point of view on stretch goals is that they are a dangerous and flawed motivational tool.

One widely reported cautionary tale about stretch goals appeared in one of the companies Collins identified as ‘great’ and superior to the rest: Wells Fargo. Around 2013, reports emerged that Wells Fargo employees were under significant pressure to reach seemingly impossible sales targets. They were being asked to ‘cross-sell’ multiple products, like savings or chequing accounts, lines of credit, credit cards, or mortgages to a single customer. The issue wasn’t the goal, but the difficulty of it: management challenged employees to sell an astronomical eight products per household, which was five times the industry average in 2013. This stretch target led salespeople to fraudulently open over 3.5 million accounts without customer permission. Cue general chaos and reputational destruction of the organization. The CEO of Wells Fargo resigned in 2016, and many other executives and employees were fired. In 2020 the company agreed to pay $3 billion in fines to the US Department of Justice, to resolve all claims related to the matter.

It turns out the Wells Fargo tragedy foreshadowed growing research evidence that identified several less desirable impacts of stretch goals.

- They induce greater risk taking.

- They increase the incidence of unethical behaviour.

- They lead to lower risk adjusted performance relative to moderately difficult goals.

- They create relationship conflict among colleagues.

- They lead to team members withdrawing commitment to the goal (i.e., giving up).

Guidance on using stretch goals

So are stretch goals a catalyst for achieving miraculous performance, or the death knell of your company’s motivation and performance?

Let’s review the possible benefits…

- Stretch goals introduce massive challenge. If there’s one thing that 40 years of goal setting research finds, it’s that more challenging goals lead to higher performance. In other words, challenge is essential for high performance. With stretch goals, you’re erring on the side of imposing more versus less challenge, which is the space where leaders seeking high performance probably need to be.

- Stretch goals spark a search for radically different ideas, knowledge, and practices. They can encourage breaking conventional assumptions, and hyper-efficient learning, all in service of generating innovation.

- Sometimes organizations need a ‘shock’ to stimulate the adoption of new processes and an increase in performance. In the absence of an external shock coming from the outside, stretch goals provide an internally generated crisis that can mobilize effort and thinking.

- Though stretch goals don’t seem to produce better performance on average, they can produce, in rare cases, unexpectedly good results. This shows up in numerous corporate examples, and in empirical research.

- Stretch goals induce risk taking. This is likely desirable in large businesses that default towards a conservative or even complacent posture of ‘if it ain’t broke don’t fix it.’ Large organizations like GE in the 1990s, or Toyota could tolerate taking risk, since they had the slack to absorb failure.

- If the process for generating stretch goals is managed well, and people are rewarded for pursuing them and not punished for failing to achieve them, they get people thinking in aspirational ways. Forget about the ‘budget’ or the ‘plan.’ What is possible? What is the limit of our performance capabilities? This was the reason Welch used these goals at GE, to break conventional and incremental thinking, and to ask people to envision performance without boundaries.

But if you’re going to use stretch goals, consider the following…

- Use stretch goals in the right situation. If you’re a company with high slack, and a track record of successful performance, you likely have the resources to pursue a ‘moonshot’ objective, and the financial cushion to absorb a failure. If you’re an organization in decline, struggling with cashflow, or experiencing setbacks, don’t submit to the temptation to set a stretch goal in hopes of reviving your company’s fortunes. For you, stretch goals will probably create panic, chaotic and disordered thinking, and demotivated team members.

- Assign your stars to work on stretch goals. These goals don’t work well for everybody. Research suggests those most motivated by stretch targets are successful, senior, and experienced. B-players may be demotivated by them.

- Stretch goals require major engineering and restructuring of the work environment. First the stretch goal team needs a high degree of autonomy and control over how to reach the goal, including the power to spend money and make decisions to change work processes. Second, senior executives need to restructure the organization in a way that clears roadblocks for the stretch team to make progress, including removing them from lengthy, bureaucratic review processes.

- Invest a huge amount of resources into supporting the stretch goal. Money, time, training, people, technology. Throw the kitchen sink at it. The level of investment towards achieving the goal should be commensurate with the difficulty of the objective.

- Leaders play a crucial role in how team members respond to stretch goals. Trust in the leader, and high support from the leader help team members respond to stretch goals as constructive challenges and not threats. Leaders also play a key role in framing stretch goals as desirable and possible, even when most doubt they can be achieved.

- Keep in mind the Jack Welch principle: reward progress towards stretch targets, but don’t punish people for failing to achieve them.

- Consider the risk/reward profile of stretch goals, and consider setting challenging goals instead. If impossible goals induce team members to take imprudent risks, engage in unethical behaviour, or just freak out, is that the risk/reward profile you want? Instead, if you set a really challenging goal, with say a 10% perceived chance of achieving it, it may still motivate people to do great things, but not cheat or break the company in the process.

- Remember the process of setting and pursuing stretch goals may be more important than the outcome. In the words of Steve Kerr, former head of training and development at GE under Jack Welch:

“It’s not the number per se, especially because it’s a made up number. It’s the process you’re trying to stimulate. You’re trying to get people to think of fundamentally better ways of performing their work.”

New workshop!

I have a new workshop titled 'How to challenge for high performance without breaking people.'

It's a half-day session designed to help leaders learn how to challenge, push, or pull their teams to the limits of their performance, but in ways that don't damage motivation, relationships, culture, and long-term well being.

I developed the content based on 37 interviews with executives from VP to CEO levels.

This material is a fit for senior or junior executives, or other high potential managers trying to achieve great things without damaging people.

Let's discuss how this fits your team's needs: tjackson@jacksonleadership.com

Music

If you were wondering what my favourite R&B themed holiday song is... well...

Further reading

Tim Jackson, Ph.D. provides advisory and deep expertise on executive leadership development to dynamic and high-performance organizations. He is President of Jackson Leadership Inc., a consulting firm located in Toronto. Tim's services include in-depth executive assessment, one-on-one executive advisory, evidence-based workshops, and facilitated sessions that create dialogue and learning among senior executives on important leadership themes.

Throughout his 19-year career, Tim has worked with CEOs, executives, and managers across Canada, the US, Europe, and China, spanning 11 industry sectors and every major functional area. Some of his clients have included BASF, Maple Leaf Foods, Husky Injection Molding, Spin Master, The Greater Toronto Airport Authority, Onex, AstraZeneca, and Algonquin Power and Utilities. Recent engagements include assessing and coaching 28 leaders in a large Canadian CPG company over 5 years, coaching senior leaders through a global chemical company's largest acquisition, and providing advisory to the CEO of a federally-funded Canadian economic accelerator.

Tim has a Ph.D. in Industrial/Organizational Psychology from Western University, where he researched the drivers of leadership effectiveness. He has published his ideas about leadership in The Globe and Mail, Forbes.com, HR Executive, SmartBrief, peer-reviewed journals, several HR trade magazines, and his newsletter at www.timjacksonphd.com.

Please feel free to contact Tim with your feedback about this site, questions about his services, or to share your own ideas about leadership in organizations.

Email: tjackson@jacksonleadership.com

Phone: 647-969-8907

Website: www.jacksonleadership.com

Newsletter: www.timjacksonphd.com

Member discussion