Dynamic balance: The conundrums of management, according to Henry Mintzberg

In my last article, I wrote about a book called ‘Simply Managing’ by the McGill University professor, Henry Mintzberg. In that article I shared some key reflection questions that Mintzberg suggested managers ask themselves in order to improve their effectiveness.

In this article I’d like to review my favourite section of that book, in which he describes 11 conundrums related to management, which can never be fully resolved, but will always lurk in the background and influence the work and experience of managers.

These principles resonated with me after observing middle managers and senior executives for many years. I think they can help managers make sense of just why their job is so difficult.

Here are the conundrums:

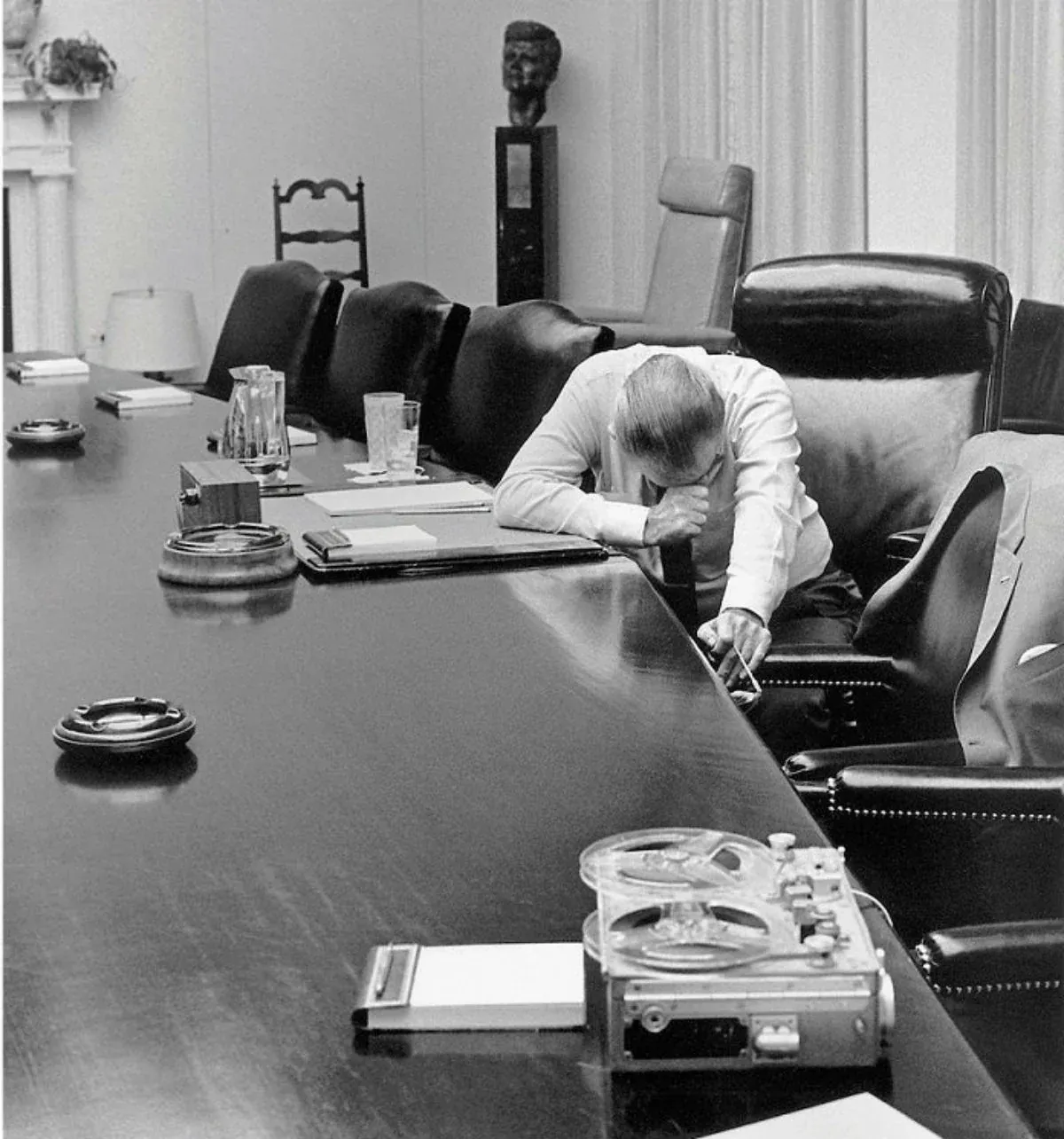

- The syndrome of superficiality: The job of managing pulls people towards acting superficially. So many decisions to face. So many stakeholders to satisfy. Relentless pressure to achieve goals. Limited time. Because of these forces, we don’t typically reward managers for their deep reflection. So one of the main occupational hazards of managers, therefore, is superficiality – i.e., thinking in a cursory way, and acting without thinking. Mintzberg questions whether so much action needs to be taken so quickly, and sometimes thoughtlessly. He urges managers to find time in their schedules to reflect on (and learn from) what they’re doing, and to break complex tasks into parts so they can consider each step with more focus.

- The predicament of planning: How are managers supposed to plan when they are constantly being dragged towards superficiality? You might think locking yourself away in your office to work through a strategic planning exercise will help. But Mintzberg says, no, managers shouldn’t detach from the organization to engage in grand, ivory tower planning sessions. Rather they should learn through action, on-the-job, and use that experience while ‘acting’ in the business to inform planning and strategy. He says great planning, strategic or otherwise, can and should happen bottom-up. Let the best plans and strategies bubble up from below, and managers can pick the best ones to execute on.

- The labyrinth of decomposition: Mintzberg argues that organizations are a world of decomposed parts – departments, functions, products, strategies, objectives, issues, budgets, etc. Everything has been atomized, separated, disaggregated, to organize and structure it. One job of the manager is to somehow put these parts together, to make them fit into a cohesive whole, like Lego pieces. But this is hard. Sometimes totally different companies merge – say one company sells pharmaceuticals, the other dog food. Or teams combine to include two unrelated functions – say marketing and operations. So how do those pieces fit together? How are you supposed to hold all-hands team meetings, and get the pharma and the dog food people to talk the same language? To address this, Mintzberg suggests managers must synthesize, take all the scattered, decomposed pieces that lay about, and combine them into a workable solution. This takes patience, and involves assembling the ‘big picture’ one small item at a time.

- The quandary of connecting: Managers by definition are disconnected from the things they manage. They’re ‘up here,’ their team and operations are ‘down there.’ So how should a manager stay ‘in touch’ and informed about the areas they have responsibility over, but which they’re alienated from? Mintzberg says we assume the biggest barriers to communication flow are ‘silos’ – vertical walls between functions or divisions. But organizations also contain ‘slabs’ – sturdy, fire-proof-grade, horizontal ceilings and floors that prevent information from flowing up and down the hierarchy. Slabs impede connecting too. To address this, Mintzberg suggests cross-pollinating: exposing those below to levels above, and managers descending levels to observe and be present (remember the phrase ‘management by walking around’?). He also says managers should see themselves as a ‘linking’ function, who transmit information up and down the organizational structure.

- The dilemma of delegating: Managers often have access to more information than those below them. To delegate to their team members, they must spend enough time conveying the important bits to their subordinates, but not so much that it saps their time. If they transfer too little, they end up doing too many tasks themselves, doing rework, or being accused of ‘dumping’ tasks. If they transfer too much, they divert time away from high value activities. To address this, Mintzberg suggests managers meet regularly with a second in command, and transfer as much information as they can in those sessions. Then, when it comes time to delegate, some of the information has already seeped towards the team member who needs it.

- The mysteries of measuring: This is a fun one. You’ve heard the cliché ‘if you can’t measure it, you can’t manage it’? Mintzberg describes how managers take a keen interest in measurable data points, favouring ‘hard,’ objective numbers. However, hard numbers can be much softer (i.e., more subjective, messy, unreliable) than they appear. Hard data tend to be highly aggregated, yet as a result lose meaning and utility. Numbers and stats often describe, but don’t explain what’s going on (for that you may need to gather some ‘soft’ gossip at the watercooler or next industry meeting). Mintzberg also says hard data can be slow to compile, and therefore less useful in the high-paced world of management. Overall, Mintzberg suggests that hard data is not as reliable and useful as it appears, and that gossip, hearsay, rumours, and other ‘soft’ information can be indispensable.

- The enigma of order: Organizations, and their managers, strive to create predictability - of products, operations, and profits. They’re asked to build systems and structures that create control, order, rules, accountability, and clarity. However, Mintzberg says the external world, which the organization must respond to, is changing relentlessly. Managers, occupying a critical role interfacing between the internal and external parts of the organization, must negotiate this tension. This manifests for managers at the team level. If they impose too much structure, their team functions in an orderly way, but is rigid and unresponsive to the dynamic forces around them. Impose too little order, and their team’s functioning, and perhaps the broader organization, descend into a chaotic maelstrom. Mintzberg suggests the solution is for managers to play both sides, to embrace change and disorder while simultaneously trying to organize it.

- The paradox of control: How can managers maintain ‘controlled disorder’ (mentioned in #7 above) within their own teams, while they're also being controlled by more senior management above? Mintzberg thinks part of the issue here is senior leadership pushing down fantastical objectives that lack realism relative to on-the-ground conditions. He describes this pattern as ‘management by deeming,’ and he’s not a fan. Idealistic goals get cascaded down and down, until they reach the lowest level managers who can’t escape realities on the ground. Mintzberg suggests managers resist these ‘deemed’ goals, either by advocating for change up the hierarchy, or in some cases disobeying.

- The clutch of confidence: Management is a tough job, filled with uncertainties (like these conundrums suggest). Therefore Mintzberg says, to offset that, the role encourages managers to project confidence. However while confidence is reassuring, too much of it can be dangerous. Mintzberg suggests managers need to figure out how to maintain sufficient confidence that it contributes to performing the job well, without projecting so much that it’s viewed as arrogance.

- The ambiguity of acting: One manager I assessed early in my career said to me “my former boss told me, ‘just make more decisions, even if you don’t know if it’s right or wrong. Don’t be a bottleneck in the organization.” As Tom Peters wrote “ready, fire, aim,” or if you prefer the modern iteration “fail fast” – i.e., take action and figure out the consequences later. The assumption is it’s important for managers to make quick decisions. Yet what happens if some of those decisions – maybe based on bad data, or flawed thinking – turn out to be wrong? Speed is great, but what are the costs of misguided decisions? Mintzberg asks ‘why do we have to make so many decisions? Can we at least break them into successive steps?’ He suggests nibbling away at decisions, step by step, piece by piece. Many actions can be taken without reaching a decision, just as a decision can be made but doesn’t have to involve immediate actions.

- The riddle of change: Managers need to create predictability and certainty for the organization, yet also facilitate change. How do you do both? Mintzberg suggests they strive to ‘manage continuity,’ adopting some changes, but maintaining connection to established administration and structures which promote stability. Managers should introduce some incremental change, while keeping continuity with the traditional order.

This article touches on the theme of 'management by deeming.'

If you're going to advocate for change up the hierarchy, this article offers some tips on how to do it.

Music

My god. This song. I don't know exactly it's meaning, but she named her autobiography after it, so I can speculate it relates to her turbulent upbringing. The lyrics are searing, suggesting a strength of will, to fight and survive, which match the dramatic melody and rhythms. (Try watching/listening while reading the lyrics.) So powerful.

Tim Jackson, Ph.D. provides advisory and deep expertise on executive leadership development, to dynamic and high-performance organizations.

Tim's services include in-depth executive assessment for development; one-on-one executive advisory rooted in his deep expertise of the drivers of leadership effectiveness; workshops on a variety of leadership topics built with evidence-based data; and facilitated sessions that create dialogue among senior leaders on important leadership themes, in an environment that promotes shared learning.

Throughout his 18-year career, Tim has worked with a wide variety of clients, including CEOs, executives, managers, and individual contributors; leaders located in Canada, the US, Europe, and China; individuals spanning 11 different industry sectors and every key functional area; and those driving major change inside private-equity owned businesses.

The following are examples of how Tim has delivered value to his clients: he assessed and coached 28 leaders in a large Canadian CPG company over a 5 year period, including preparing high potentials for promotion and helping derailing leaders course correct; he coached senior leadership team members and middle managers in a global chemical company to navigate dynamic change resulting from the largest acquisition in their history; and he provided assessment, coaching and advisory support to the CEO of a Canadian ‘supercluster,’ a federally-funded accelerator of strategic economic activity (this cluster received renewed funding in early 2023).

Tim has published his ideas about leadership in various outlets, including The Globe and Mail, Forbes.com, several HR trade magazines, and peer-reviewed journals. He also writes original articles about leadership topics in his newsletter at www.timjacksonphd.com. He has also shared details about his practice at leading conferences like the Society for Industrial and Organizational Psychology.

Tim has a Ph.D. in Industrial/Organizational Psychology from Western University, where he explored the drivers of leadership effectiveness in both his Master’s and Dissertation-level research. He and his family are based in Toronto, ON.

Please feel free to contact Tim with your feedback about this site, questions about his services, or to share your own ideas about leadership in organizations.

Email: tjackson@jacksonleadership.com

Phone: 647-969-8907

Website: www.jacksonleadership.com

Newsletter: www.timjacksonphd.com

Member discussion