My leadership philosophy - Part 5: Situational and contextual leadership

[This article is part of a series in which I'm sharing key lessons I've learned about what drives or derails effective leadership, distilled during my 17 year career assessing and coaching executives. Previous articles included an introduction to the series, a focus on charismatic/inspirational leadership, a summary of transformational leadership (with mention of two complimentary styles called contingent reward and instrumental leadership), a summary of tactics leaders can use to project greater charisma, and a discussion of the importance of relationships to leadership.]

Introduction

How would each of the following situations affect the way you lead (if at all)?

Imagine… You’ve been promoted to a new role. The new group of direct reports you’re leading are all male. You are female.

Imagine… As a Canadian executive, you’ve been transferred to a leadership role in Brazil. Compared to the culture you’re coming from, Brazilians prefer that their leaders build very close relationships with them and consult the group before making most decisions.

Imagine… You’ve led teams in a face-to-face work environment your entire career. One day your boss asks you to take on a global role in which you’ll be managing direct reports located all over the world, in a 100% virtual manner.

These vignettes represent some of the complex situational factors which confront leaders on a frequent basis. How should they identify and navigate these dynamic environmental forces?

In this article I’ll explore this topic further in several ways. First, I’ll argue that situational dynamics are important for leaders to pay attention to in part because they determine the definition of leadership effectiveness for a given scenario. Then I’ll present a framework leaders can use to diagnose the context around them. Next, I’ll share three possible response patterns that leaders might engage in, based on understanding their situational milieu (i.e., adjusting their behaviour, seeking a match, or engineering). Finally, I’ll offer practical suggestions on how leaders can attune themselves to the situational dynamics swirling around them.

Situations influence definitions of leadership effectiveness

Why should leaders care about ‘the situation’? One key reason is that situational conditions seem to influence people’s expectations of leaders, and shape the way they judge their effectiveness.

One example of this emerges from research on how societal culture shapes preferences for leadership style. As found in the GLOBE project, each society possesses a kind of ‘mental scorecard’ for what effective leadership looks like, influenced in part by their culture. To illustrate, people from China prefer leaders who build strong social ties (even with the team's family members); Brazilians like participative and consensus-building leaders; meanwhile the French expect leaders to take a formal, impersonal and hierarchical approach to relationships.

Crisis situations also seem to influence preferences for leadership styles. Based on my professional experience, team members seem to tolerate much more assertive and directive leader behaviour under conditions of existential threat. In these cases, most understand the costs of inaction are extreme, the desire to reduce uncertainty is high, and so many will forgo their individual rights to influence the decision. Getting even more specific, some researchers even suggested that different kinds of crises may generate specific expectations for leaders. For example, in crises emanating from outside the organization, and which are unintentional (e.g., Covid), leaders are expected to act as ‘shepherds’ who protect, guide, and make sense of the crisis. In crises coming from outside the organization but which are intentional (e.g., September 11th terrorist attack), leaders need to act as ‘saints’ and help others manage a wide range of negative emotions, and to provide comfort and support. For internal-unintentional crises involving incompetence (e.g., a product recall), leaders need to act as a ‘spokesperson’ and apologize. Finally, for internal-intentional crisis (e.g., Enron fraud), the leader is labelled a ‘sinner’ and needs to resign quickly.

As a final point, there have been hundreds, perhaps thousands of studies of leadership over the years examining ‘moderator’ variables. These represent different conditions which might influence leadership effectiveness (e.g., type of organization, gender composition of teams, profitability to name just a few). Often these studies find that leadership is more or less effective in one condition or another. There could be many reasons that account for this, but one plausible consideration is that different kinds of conditions change followers' expectations of their leaders.

What is 'the situation'?

If it’s important for leaders to take account of ‘the situation,’ what characteristics should they pay attention to?

A researcher named Gary Johns (with some refinement from another researcher named Burak Oc) created a framework for understanding contextual factors which can help leaders consider what situational dynamics might be present.

The framework is divided into two kinds of contextual variables, omnibus and discrete. Omnibus variables are characteristics which are further removed from or more distal to a leader (e.g., societal culture), but which nonetheless may impact them. Discrete variables are relate more to a leader’s immediate or proximal environment (e.g., the internal climate within the team).

Below I’ll describe each part of the framework and suggest reflection questions intended to deepen thinking about that variable.

Omnibus

Who?

1. Gender composition – e.g., what proportion of my organization is male vs female, and how does this composition influence norms or expectations for leaders (if at all)?

2. Other demographic differences – e.g., what proportion of my organization is made up of younger vs older generations, higher vs lower income, or those educated above vs below the high-school level? How do these demographic characteristics influence the kind of leadership behaviours others would like to see?

Where?

1. National culture – e.g., what are the predominant societal cultural characteristics of the country I’m working in (e.g., individualistic vs collectivistic, hierarchical and status conscious vs egalitarian), and how does this backdrop affect the kind of leadership style my team might prefer?

2. Institutional forces – e.g., is the business environment I’m working in highly regulated or more permissive (think railroad vs startup), and to what extent does this influence preferences for leadership styles?

3. Type of organization – what type of organization do I work in (e.g., bureaucratic, entrepreneurial, voluntary, or professional service), and how does that identity influence expectations of leaders?

When?

1. Organizational changes – e.g., what kinds of organizational changes are taking place around me, and how does this influence the kind of leadership others need or want?

2. Organizational decline – e.g., to what extent is the organization or market I’m working in experiencing decline, and if it is, how does this change the type of leadership required?

3. Economic conditions – e.g., what are the broader economic conditions surrounding my organization (e.g., growth vs recession; stable vs unstable), and how might they impact the leadership others want to see from me?

Discrete

Task

1. Task characteristics – e.g., how structured, ambiguous, or challenging is the task, and what does this imply for the kind of leadership style I should express?

2. Job characteristics – e.g., are the people I’m leading used to working in conditions of high vs low autonomy, feedback, or identification with their work, and how might this influence their preferences for leadership?

Social

1. Team and organizational – e.g., what is the internal social environment/climate like within the team and the organization, and how does this impact expectations for leadership?

2. Social network characteristics – e.g., am I or is my team a key part of the social network of the organization – does information need to pass through us, do people need to check key decisions with us, do we have many strong relationships with key stakeholders – and if so how does that influence how I might lead?

Physical

1. Physical distance – e.g., to what extent is the team I’m leading remote from each other and from me, and how does this impact how I should lead them?

Temporal

1. Time pressure – e.g., to what extent is my team working under time pressure, and if they are, how does that influence the leadership style they might prefer to see from me?

Three ways leaders can respond to situational dynamics

Once a leader cultivates awareness about the situation that surrounds them, the next challenge is to decide how to lead in light of that information.

For clues about how leaders might respond across contexts, we can examine several early situational leadership theories.

While some of these theories suffered from too much simplicity or complexity, or not enough empirical support, they made valuable contributions by emphasizing the importance of situational awareness, and by suggesting different ways leaders could respond to their environments.

In this section, I’ll highlight three possible response strategies, and provide examples of theories that illustrate each approach.

Leader flexibility

One way a leader can respond to situational dynamics is to adapt or flex their behaviour to suit the environment.

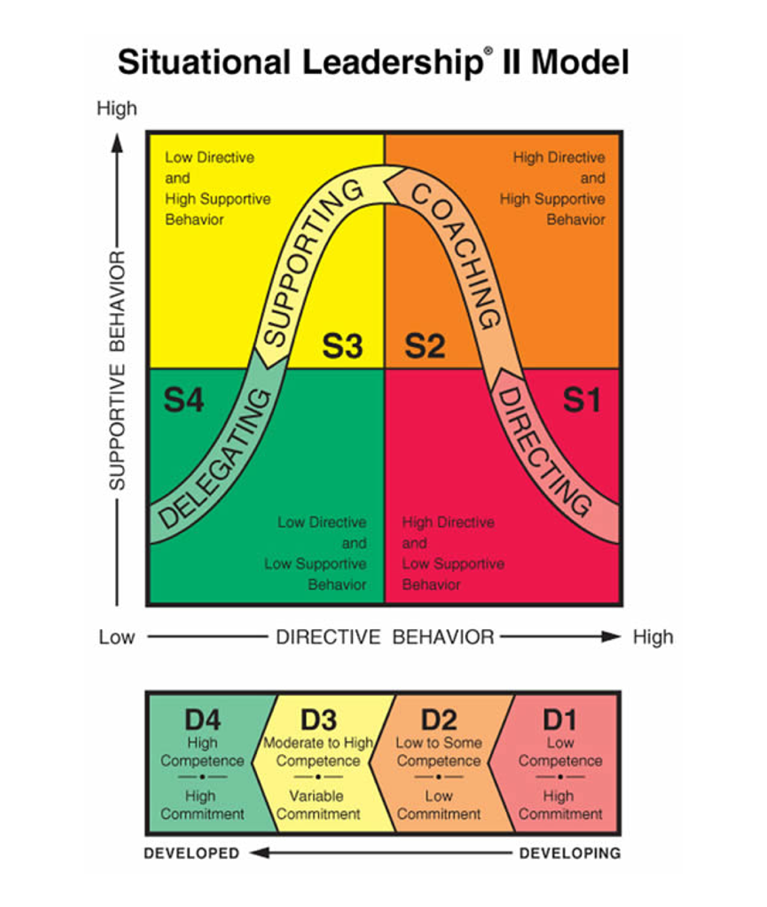

This response is emblematic of situational leadership theory. In this theory, the key situational factor is the ‘maturity’ of a leader’s subordinates. The model says leaders need to assess this quality to decide what mix of task- or relationship-oriented behaviour to use. A high-maturity subordinate has the ability and confidence to do the task, while a low-maturity subordinate doesn’t. When the subordinate is immature vis a vis the task, the leader should adopt a task-oriented approach only, by defining roles, clarifying standards, and monitoring progress. Under conditions of medium maturity relative to the task, the leader can use fewer task- and more relationship-oriented behaviours, including being supportive, consultative, and offering praise. When the subordinate is highly mature, the leader can minimize both task- and relationship-oriented behaviours.

Although the creators of the theory emphasized that leaders can develop their subordinates’ skills (i.e., they’re not fixed), the core assumption of the theory is that leaders needs to adapt and adjust their behaviour based on their subordinates.

Leader-match

Another way a leader can respond to the situation around them is to try to find a match between their style and the scenario.

A framework called cognitive resources theory provides an example of this response. In this theory, the key situational factor is the level of stress experienced by the leader. The theory examines how well two traits, the leader’s intelligence and experience, contribute to their effectiveness under conditions of varying stress. The model states that under high stress (e.g., frequent work crises, conflicts with team members), the leader’s level of experience (not intelligence) will influence their decision quality. By contrast, under low stress, the leader’s intelligence (not experience) will influence their decision quality.

This framework assumes that the leader possesses relatively stable traits (i.e., intelligence and experience), and instead of adapting to the context, they might instead work to place themselves in situations that best ‘fit’ their skills. So for example, the framework might suggest that highly intelligent but inexperienced leaders should do whatever they can to avoid stressful situations. Putting yourself in situations in which you’ll be less effective means you’re ‘not matched’ or poorly fit to the situation. Placing yourself in situations in which you’ll be more effective means that you’re ‘in match.’

Situation engineering

The final response pattern involves leaders engineering the situation so that the conditions meet their team members’ needs, making the leader’s role less necessary or even redundant.

An example of this approach is the ‘substitutes for leadership’ theory. This way of thinking says ‘the situation is all powerful, and there’s more return on investment from engineering the system and the situation than engaging in any leadership behaviours.’ The theory suggests that certain situational characteristics are so potent that they can either substitute for, or nullify the influence of leadership. For example, if a team member is working on a task they truly love, then they may not need supportive leadership. Or if a team member is working on a highly structured or routine task, then they may not need much task-oriented leadership. In these examples, the rewarding and highly structured tasks are ‘substitutes’ for leadership. In a different kind of situational influence, if a team member doesn’t care about the rewards the leader can offer, this indifference would nullify or neutralize the leader’s ability to motivate them.

If you accept that the situation is all powerful, this implies that leaders should spend their time engineering and redesigning the environments surrounding their teams. For example, leaders should hire experienced and capable team members, and provide high quality training, to make constant coaching unnecessary. Or they should spend more time formalizing roles and procedures, to minimize the need to provide clarity to their teams. Furthermore, they should use rewards that they know will motivate their teams, so that if they do express their leadership, that it has a greater positive effect.

In summary, several early leadership theories made helpful contributions by emphasizing the importance of situational awareness, and in particular different ways leaders can respond to their environments.

Practical suggestions

In this section I’ll offer several practical suggestions on how leaders can sharpen their appreciation of the contexts they’re working in.

Increase situational awareness

If the context shapes the criteria or scorecard for effectiveness, leaders may want to push themselves to increase the depth and breadth of their situational awareness. Gathering richer environmental information should illuminate the best leadership path forward.

One way to do this might be to use the omnibus/discrete framework as a checklist to uncover and raise awareness of situational dynamics. When faced with a significant leadership challenge, leaders could use a blank piece of paper to write down all the omnibus and discrete factors that lurk around their challenge. After making these notes, leaders could ask ‘what do these factors suggest about how I should lead others in this scenario?’

Remember the omnibus context

In my experience leaders are skilled in monitoring contextual variables in their immediate environment. However the peripheral omnibus variables can also play a meaningful role in shaping what people want from their leaders.

So another possible suggestion is for leaders to exert special effort to scrutinize the distal omnibus factors surrounding them, in addition to the immediate situational dynamics.

Consider all the response options

When faced with a leadership challenge, remember that leaders can respond in several ways. The most common assumption these days is that leaders should adapt and flex their style to those around them. In addition to this, however, leaders could also consider inserting themselves into only those situations that best fit their skills. Also they can choose to prioritize engaging in more systems-based situational engineering, by designing and creating the optimal conditions that will help their team succeed.

Balance keeping a core, and finding ways to flex

While I’ve emphasized the power of the situation in shaping expectations for leadership, and outlined how leaders should shift their style in response to their environment, there are limits to this perspective.

I believe that one of the key challenges of leadership is to maintain a firm set of core principles, while also being willing and able to bend to the conditions.

Too much flexibility could lead to the perception of inconsistency or inauthenticity. Too much adherence to core principles could lead to nonadaptive behaviour and perceptions of rigidity. In the end, paradoxically, perhaps leaders need to do both.

Conclusion

In this article I’ve described how situational factors may shape the leadership qualities we value, and that leaders need to be aware of and adjust to these forces.

I shared a framework that can help leaders identify various contextual factors that might impinge upon them.

I also shared several possible ways in which leaders could respond to their environments, by flexing their behaviour, seeking a match with their profile, or engineering the situation and system around them.

Finally, I also shared some practical suggestions on how leaders could enhance their attunement to their environments.

I hope these perspectives and suggestions help you to consider your context in new ways, and reveal insights on how you might adapt your leadership behaviours to it.

As always I would welcome your feedback, positive or constructive, on anything you read, and I would love to learn from your perspective.

If you’d like to comment on this article, you can do so below. In order to comment, you’ll need to enter your name and email address, and to click a confirmation email you receive, a process that ensures you’re real and not a robot (you won’t need to create a password). If you prefer you can also email me your feedback at tjackson@jacksonleadership.com.

Thank you for reading. If you’d like to receive these newsletter issues direct to your inbox, please click the blue ‘Sign up now’ button below.

Tim Jackson Ph.D. is the President of Jackson Leadership, Inc. and a leadership assessment and coaching expert with 17 years of experience. He has assessed and coached leaders across a variety of sectors including agriculture, chemicals, consumer products, finance, logistics, manufacturing, media, not-for-profit, pharmaceuticals, healthcare, and utilities and power generation, including multiple private-equity-owned businesses. He's also worked with leaders across numerous functional areas, including sales, marketing, supply chain, finance, information technology, operations, sustainability, charitable, general management, health and safety, quality control, and across hierarchical levels from individual contributors to CEOs. In addition Tim has worked with leaders across several geographical regions, including Canada, the US, Western Europe, and China. He has published his ideas on leadership in both popular media, and peer-reviewed journals. Tim has a Ph.D. in organizational psychology, and is based in Toronto.

Email: tjackson@jacksonleadership.com

Web: www.jacksonleadership.com

Newsletter: www.timjacksonphd.com

Member discussion