My leadership philosophy - Part 7: Directionality

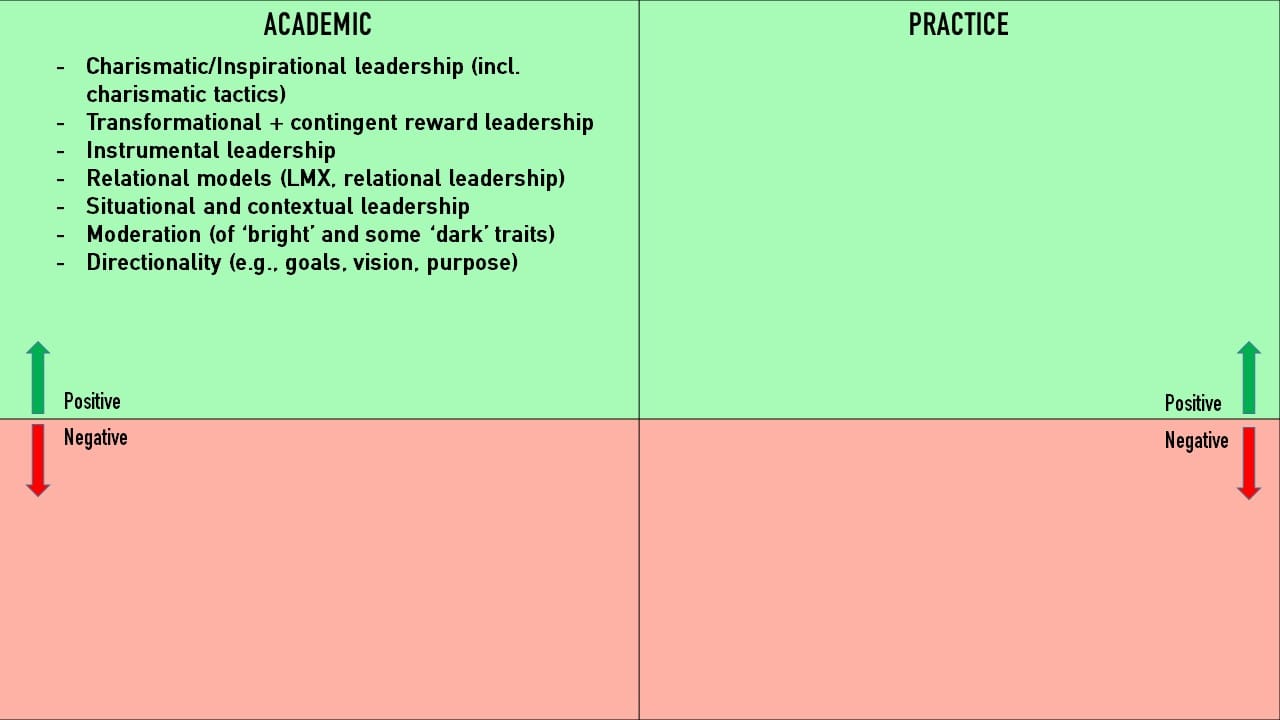

[This article is part of a series in which I'm sharing key lessons I've learned about what drives or derails effective leadership, distilled during my 17 year career assessing and coaching executives. Previous articles included an introduction to the series, a focus on charismatic/inspirational leadership, a summary of transformational leadership (with mention of two complimentary styles called contingent reward and instrumental leadership), a summary of tactics leaders can use to project greater charisma, a discussion of the importance of relationships to leadership, a review of the role of situational and contextual influences on leadership, and a description of how moderation may contribute to effective leadership.]

Introduction

I consider leadership, at its most minimalist, to involve two basic ingredients: first a goal, vision, purpose, or sense of direction representing what a leader wants to accomplish; and second an ability to motivate others to travel in that direction. On the first point, I will concede, men and women can occupy positions of power while also lacking their own unique direction. In those cases, they might strive to preserve continuity with the status quo, or to respond to whatever the environment presents. However, one could argue that such behaviour isn’t leadership, but rather caretaking, reactivity, or malleability. By contrast, think about great and effective leaders for a moment, and ask yourself if you can recognize their direction, what they wanted to accomplish, or what they stood for. Often these leaders embody, and show intentionality towards a compelling goal, vision, or purpose. Abraham Lincoln sought to preserve the Union during the civil war. Mahatma Ghandi wished for a free and independent India. John F. Kennedy endeavoured to land humans on the moon. Churchill sought peace and victory in Europe. Nelson Mandela worked to end apartheid. Can you name one great leader who was directionless, aimless, adrift? Indeed, directionality seems to be a necessary requirement for effective leadership, without which leadership ceases to exist.

In this article I’ll make the case that directionality, in the form of defining an objective or standard whether in precise or abstract ways, is an essential part of effective leadership. At the same time, I’ll explore how leaders can express directionality in many ways, including using goals, vision, and purpose. I’ll describe and compare each of these forms of directionality in turn, and at the end of the article share some suggestions on how leaders can use these insights to benefit their own practice.

Goals

What are goals?

Goals have two defining characteristics. First, they establish an objective that is discrepant from the status quo. The degree of distance between the status quo and the goal represents the goal’s challenge, difficulty, or tension. Researchers believe that goals are powerful motivators in part because goal-setters feel discontent in proportion to this discrepancy, which in turn energizes them to reduce that gap by achieving the outcome in question.

A second characteristic is that goals are specific, precise, and measurable. One important operationalization of this specificity often involves imposing a limited timeframe for achieving the goal. (As we’ll see later on, other forms of directionality – like vision and purpose – represent some desired change from the status quo, but don’t emphasize specificity or time boundedness in the same way.)

While leaders often use goals to direct tasks for individuals, another important characteristic of them is that they can apply equally well to teams and organizations. Goals 'scale' well from individuals to larger collectives.

Goals are central to effective leadership

Most theories of effective leadership include descriptions of setting and facilitating goal achievement. Examples of such theories include initiating structure, path-goal theory, transformational leadership, charismatic leadership, contingent reward leadership, and servant leadership.

According to these theories, effective leaders set challenging goals, frame goals in inspiring ways, show confidence that others will achieve goals, specify the rewards flowing from goal attainment, and animate groups to work together to reach goals.

In addition, research also suggests that overly passive and avoidant leaders who are unavailable to provide direction when needed, are rated as highly ineffective.

Studies on leadership and goals tend to examine the goals in a variety of ways, including in terms of clarity, stretch/difficulty, specificity, goal commitment (a key outcome for leaders to generate in others), collective vs personal focus (i.e., does goal attainment benefit the collective or just the individual leader?), and goal congruence (e.g., does a person agree with the organization's goal, or do team members agree with each other on the importance of the goal?).

Goal-focused leadership fills gaps in previous thinking about leadership

While many prominent theories of leadership specify the importance of goals, few emphasize the intuitive idea that goals set by leaders should be clear.

A recent conceptualization of leadership called goal-focused theory fills this gap.

Goal-focused leadership involves clarifying goals (including roles and responsibilities), linking goals with higher order objectives of the organization, and then helping employees translate those goals into concrete plans and priorities.

As you might discern, this approach to leadership focuses less on setting a goal (and perhaps presumes most leaders receive directionality from their superiors), and more on clarifying the meaning, interconnectedness, and operationalization of those goals. The assumption is that this leadership approach is effective because it helps team members focus their efforts on the most organizationally valued activities.

I suspect this form of leadership resonates with the ‘real world’ experience of many middle and senior managers in large organizations, who spend much of their time engaging in similar goal facilitation activities (rather than more inspirational leadership behaviours).

The curious case of stretch goals

As mentioned above, one key characteristic of goals is the amount of challenge, difficulty, or tension embedded in them. This represents the degree of discrepancy between where you are, and where you want to go. Research suggests that the higher the discrepancy, the greater the motivation. But what happens when that discrepancy becomes extreme?

One term that’s been used to describe goals with an extreme degree of difficulty is ‘stretch goals.’ Stretch goals have often been used to describe organizational-level objectives that leaders set, with an unknown but seemingly impossible probability of attainment. In other words, when hearing about a stretch goal for the first time, most people think there’s a 0% chance of achieving it, given the current capabilities and knowledge of those in the organization. (By contrast, ‘challenge’ goals have been defined as goals that have a perceived 10% chance of attainment.)

The assumed value of stretch goal is that their introduction sparks an internally generated crisis in the organization, which leads to a vigorous search for and learning of radically innovative strategies.

I can share two examples of this. The first involves Southwest airlines. Early in its history, after being forced to sell part of its fleet, Southwest Airlines decided to set a bold stretch goal to increase its performance: ten-minute turnaround times for their airplanes at airport gates. Although most observers viewed this stretch goal as unachievable, Southwest ultimately achieved it by adopting practices from race car pit crews, which to that point had never been applied to the airline industry.

In a second example, Jack Welch once described a stretch goal he set for his company, General Electric, to increase it's margins:

“We have what we call stretch targets. . . . For example, we spent 105 years in this company and we never had double digit operating margins. We said in 1991 we want 15 and we put it in our annual report. We told everybody. 9.6 or 9.5 was our best. We’ll do 14 in 1994, and prices have been going down in the global market. And we’ll do 15 next year. We never did more than 5 inventory turns and we said we’ll do 10. We had no idea how we would get to 10. . . . The big line I use today is that budgets enervate and stretch energizes. It’s real.”

(Notice how these stretch goals are very precise, and in the Jack Welch example contained a specific timeframe.)

Organizational stretch goals, especially the successful examples mentioned above, are compelling, almost myth-making reading. At the same time these goals introduce tremendous ‘motivational risk,’ should team members come to believe they’re unrealistic or unattainable. What is the cost on people, turnover, morale, when attempts to pursue extreme stretch goals fail? And perhaps more important, stretch goals can introduce existential risk, if taken on by organizations that can’t tolerate the shocks involved in pursuing them, or the failure of not attaining them. These tradeoffs need to be considered before leaders set any stretch goal for their organizations.

Vision

What is a vision?

Visions are idealized images of a future state, which invoke values, core ideology, identity, and followers’ or the collective’s needs.

They can be written or articulated in an evocative manner, that stimulates the senses. As such, they may contain content that enhances their vividness and appeal, such as image-based rhetoric (i.e., words or phrases that elicit a sensory experience), metaphors, values, references to the past/present/future, and optimism.

How is a vision different than a goal?

Visions tend to focus more on animating collective (not just personal) action, while goals could be used to motivate either individual or collective effort.

Visions may set direction in a way that’s less specific or measurable compared to goals (think of the phrase ‘visions are more qualitative; goals are more quantitative’). The pursuit of visions can therefore become ongoing, and the vision may never be fully realized or achieved.

‘Visions are more qualitative; goals are more quantitative.’

There is a persuasive element to visions. They're often described in terms of not only their content but also their articulation. There’s a sense that a vision is meant to influence or inspire others, to attract them to the future state. Goals may not necessarily contain this persuasive content.

Also visions tend to focus on longer-term time horizons, while goals can assume either a short- or long-term focus.

What is the function of a vision?

Why do organizations need visions? Why layer visions on top of organizational goals? Why can’t organizations just write a detailed list of company goals to establish their directionality, like Jack Welch’s objective to increase margins? And why can’t all the divisions and functional areas within an organization just set their own goals, independent of any larger cohering vision?

Warren Bennis, the great leadership scholar, thinker and authour, encapsulated several compelling reasons why organizations need visions, in his book ‘Leaders’ which he co-authoured with Burt Nanus:

- First, he said that visions form the basis for collective action. Bennis wrote that by definition organizations are groups of people engaged in a common enterprise, and so there needs to be some harmony amongst their actions. A vision relates to all parts and pockets of a company, inclusive of all the disparate goals, interests, and objectives within its various divisions, and unifies them under one shared direction. Vision creates the basis for organized collective action.

- Second, he suggested that visions provide clarity. He described how organizations and their members face two fundamental challenges – for the entity to find its niche in the external environment, and for its employees to identify their roles within that entity. All this ‘role-seeking’ can create considerable confusion. A vision, he said, helps members of a company identify their roles both within the organization and the broader society. A vision creates focus and clarity related to roles, tasks, priorities, and the measurement of progress.

- Visions also help team members create meaning about their affiliation with the organization. If team members endorse the vision, they feel pride and even status from contributing to it.

- Finally, visions create a basis for decentralized and efficient action. If a leader knows a potential decision will align with the vision of the company, they can act on it without seeking approval.

How do leaders create high-quality visions?

Surprisingly, there isn’t evidence-based consensus about how to create a great vision, or what component parts should be included in it. However, based on work by a researcher named Michael Mumford (and his many colleagues) at the University of Oklahoma, we can make some educated guesses about how to formulate a vision:

- The first step of vision formation is often the experience of a crisis or change in the organization.

- Second, leaders should seek to understand this crisis by reflecting on their current mental model of the organization and the ‘system’ surrounding them. This is called a ‘descriptive’ mental model and represents the leader’s perception and understanding of the status quo. Leaders create these models through accumulated experience, their values and perceptions about the needs of others.

- Third, by reflecting on this ‘descriptive’ model, leaders should begin to think about two important questions: 1) what goals should the collective or organization pursue, in light of this crisis?; and 2) what causes or determinants will influence the attainment of those goals? Reflection on both goals and causes/determinants, in the context of the crisis, will help the leader generate a new perspective on the organization called a ‘prescriptive’ mental model, which represents the desired future state. This 'prescriptive' model forms the foundation for the vision.

- Fourth, before leaders create a vision statement, they need to take one further ‘late-stage’ refinement step called forecasting. In this step, leaders identify more vs less effective actions that might flow from the ‘prescriptive’ model, and use insights about them to further strengthen the emerging vision. In practice, leaders can perform this step by a) creating a preliminary plan of action based on their ‘prescriptive’ model, and then b) forecasting what might happen in the future, based on that plan. Leaders should create extensive forecasts, that are complete, detailed, and address several possible outcomes. In addition, when conducting the forecasts leaders should adopt a long-term time horizon, and consider what resources might be needed to achieve their plan.

- Fifth, leaders should revise their ‘prescriptive’ model based on any learnings gleaned from the forecasting exercise.

- Sixth, leaders should then create their vision statement. The statement can be anywhere from a sentence to a short paragraph in length.

‘Where the sidewalk ends’

As a final note leaders should remember that vision formation, in the final stages, involves an act of faith. For all the listening, environmental scanning, and data collection that visioning involves, leaders will reach a point where the path lighted by the data peters out, and leaders (or a small group of them) must ‘choose’ the way forward. Ultimately visions are a projection into the future, a gesture that involves inherent uncertainty and risk.

Purpose

What is purpose?

The term purpose can be interpreted in at least two different ways.

First, purpose can be used as a synonym for directionality. With this way of thinking, purpose is an umbrella term that encompasses any kind of direction set by a leader, including vision, mission, and values, among others.

A second way to think about purpose is as a further broadening of directionality as I’ve conceived it here. In particular, purpose can be defined as directionality that strives to integrate the organization with the surrounding society in which it sits, and in the process connect with the moral, ethical, and values frameworks embraced by that society. In other words, what’s unique about purpose is its focus on intertwining directionality with the social context external to the organization, and with the moral and ethical principles of that ‘outside’ society.

This second definition of purpose begs a deeper philosophical question: “what is the leader, and the organization he or she guides, ultimately responsible for?” Should the leader interpret their responsibilities, and set their directionality, based on a narrow and self-interested agenda – in a way aligned with the Nobel Prize winning University of Chicago economist Milton Friedman, who famously asserted that the social responsibility of business is to increase its profits? Or should leaders interpret their responsibilities, and set their directionality, based on a desire to exist in harmony with the broader societal and moral fabric?

A testy exchange between Milton Friedman and a student at Cornell University in 1978, in which they discuss the case of a man in Ohio passing away after having his electricity turned off on account of being unable to pay his bill. The debate touches on the question of whether organizations have moral responsibilities to the wider societies in which they operate.

How is purpose different than goals and vision?

As mentioned, purpose involves an alignment with the moral and ethical principles of the social context. By contrast, discussions of goals and vision in leadership research don’t require this same focus.

Also, the alignment of purpose with the world external to the four walls of the organization is unique. Purpose carries assumptions that business is a part of society and not separate from it; that it exists with the permission of society; and that organizations should contribute to the common good of the broader collective (not just to their own self-interest). These assumptions are radically different than those embedded in typical goals and visions.

Yet another distinct characteristic of purpose is that the moral and ethical principles it aligns with are incredibly relational, collective, humane, caring, and egalitarian in their orientation. Goals and visions don’t always share these qualities.

Goals- vs Duty-based purpose

If we choose to think about purpose is as an overarching umbrella term that encompasses all forms of directionality (i.e., as a synonym for the term directionality), we might consider categorizing purpose into forms that focus either on the organization’s internal interests only, or on broader society’s welfare. These forms can be labelled goals- or duty-based purpose, respectively (see this paper by Gerard George of Georgetown University and his colleagues, for more details).

Goals-based forms of purpose represent an organizational objective chosen by the firm, without recognizing the wider role of the firm in society as a moral actor (think Milton Friedman). Goals based forms of purpose could include the following:

- Mission: Describing why the company exists (heavy emphasis on this first part), what it's striving to accomplish, what it stands for, and how it plans to achieve its objectives.

- Vision: (We’ve covered this above, so I won’t repeat the definition.)

- Strategic intent: A statement that focuses on beating the competition. It focuses on winning, and captures what it means to ‘win.’ It’s also stable over time, and sets a clear target.

Duty-based forms of purpose are influenced by societal values, link with wider societal responsibilities, and align with moral/ethical obligations. These forms of purpose could include the following:

- Values: These define how people and organizations should act and interact with others. They also represent the intrinsic beliefs and core principles that decision makers should reference. Values define which behaviours are ‘good’ vs ‘bad,’ and ‘how we’re going to act on the way to our destination.’

- Social service: This represents a kind of purpose created by organizations that focus on creating social, more so than commercial benefit. These purpose statements might be used by charitable or social sector organizations.

- Sustainability: This represents purpose that focuses on being environmental stewards of the planet, and considering the welfare of future generations in a firm’s dealings, operations, and creation/delivery of products and services. (Can you imagine someone asking Milton Friedman if a corporation should concern itself with the welfare of people living several generations into the future? It might be an awkward moment.)

Practical recommendations

Based on the preceding discussion of directionality, I’d like to make several practical suggestions for how leaders can put this knowledge to use.

Use goal-focused leadership

As a leader, if you don’t already, consider using the principles of goal-focused leadership. Spend time clarifying goals for your team (including their roles and responsibilities). Link the goals of individual team members with higher order objectives of the organization (including how they relate to the mission or vision of the organization). And help team members translate those goals into concrete plans and priorities.

Balance realism and difficulty when setting goals

Goals need to be calibrated such that they challenge team members to the point of discomfort. However, they also need to contain enough realism that team members believe they can achieve them, and therefore can develop commitment to the objective.

Set at least one ‘challenge’ goal for your team

Stretch goals may be a bridge too far for most. Frankly for some organizations that don’t have considerable reputational prestige and slack resources (i.e., cash on hand), stretch goals are likely dangerous. Challenge goals may offer a more constructive stimulus to your organization or team, without the motivational or existential risk. Used in smaller doses, they might generate outsized results with reduced risk.

Create a vision for your team

Follow the process outlined above and write down your ‘descriptive’ model of the current state, followed by the ‘prescriptive’ model of where you want to go. Make sure you capture goals and possible determinants of attaining those goals. Sketch a tentative action plan based on your ‘prescriptive’ model, and then perform an extensive forecast about that plan. Try to foresee as many details as possible about how your ‘prescriptive’ model will play out, including long-term outcomes, and what resources you may need. Finally, craft a short vision statement, using evocative language, and containing values, metaphors, images, and optimism, as well as references to the collective and to the past/present/future.

See if you can write down your organization’s purpose, mission, vision, values, strategic intent, and commitment to sustainability/stewardship

If you can articulate these statements, as a follow up, ask yourself:

- What am I clear about, and what am I fuzzy about?

- In writing these, what did I realize about what’s important to me as a leader, and to my organization?

- What about these statements 'feel good' to me as a leader, and how can I share that positive energy with my team?

- What goals do these statements suggest I should set for myself or my team?

Conclusion

In this article I’ve explored the various ways in which leaders can provide directionality to others, moving from more precise forms like goals, towards less time-bounded and more abstract versions like vision and purpose. In terms of goals, I’ve described their centrality to many theories of effective leadership, introduced a goal-focused leadership style that focuses on clarifying and facilitating goals, and discussed the allure and risks of organizational stretch goals. For vision, I described how it differs from goals, its function in organizations, and a process for creating your own statement. For purpose, I explored how this concept differs from both goals and vision, and shared an organizing framework for categorizing different forms of purpose. Finally I’ve offered some practical suggestions for how leaders can utilize goals, vision and purpose in their efforts to guide others.

I hope these ideas encourage you to think more deeply about the directionality you bring to others as a leader, and how to make better use of its multiple forms.

As always I would welcome your feedback on anything you read, and I would love to learn from your perspective.

To share you thoughts you can leave a comment at the end of the article, or if you prefer you can also email me your feedback at tjackson@jacksonleadership.com.

Thank you for reading. If you’d like to receive these newsletter issues direct to your inbox, please click the blue ‘Sign up now’ button below.

Appendix A

If you found the previous Milton Friedman video interesting, and want to feel even more squeamish, try watching the continuation of his debate with the same Cornell student in 1978. In this segment, the student asks about Ford's decision to knowingly refrain from installing a plastic part in a car called the Pinto, that would have protected the gas tank from exploding after a rear end collision. The ensuing discussion I think provides a deeper examination of the question of what a leader, and their company's responsibility is to the society in which it's a part.

Appendix B

The following are the specific behaviours included in the goal-focused leadership construct:

- Providing direction and defining priorities

- Clarifying specific roles and responsibilities

- Translating strategies into understandable objectives and plans

- Linking team mission to org mission

- Following up to ensure execution.

Tim Jackson Ph.D. is the President of Jackson Leadership, Inc. and a leadership assessment and coaching expert with 17 years of experience. He has assessed and coached leaders across a variety of sectors including agriculture, chemicals, consumer products, finance, logistics, manufacturing, media, not-for-profit, pharmaceuticals, healthcare, and utilities and power generation, including multiple private-equity-owned businesses. He's also worked with leaders across numerous functional areas, including sales, marketing, supply chain, finance, information technology, operations, sustainability, charitable, general management, health and safety, quality control, and across hierarchical levels from individual contributors to CEOs. In addition Tim has worked with leaders across several geographical regions, including Canada, the US, Western Europe, and China. He has published his ideas on leadership in both popular media, and peer-reviewed journals. Tim has a Ph.D. in organizational psychology, and is based in Toronto.

Email: tjackson@jacksonleadership.com

Web: www.jacksonleadership.com

Newsletter: www.timjacksonphd.com

Member discussion