My leadership philosophy - Part 8: Culture is the scorecard

Preamble

This article is part of a series in which I'm sharing key lessons I've learned about what drives or derails effective leadership, distilled during my 18 year career assessing and advising executives. Here is an index to previous articles in the series:

- An introduction to the series.

- Part 1: Charismatic/inspirational leadership.

- Part 2: Transformational leadership (also mentioning two complimentary styles, contingent reward and instrumental leadership).

- Part 3: Tactics leaders can use to project greater charisma.

- Part 4: A discussion of the importance of relationships to leadership.

- Part 5: A review of the role of situational and contextual influences on leadership.

- Part 6: How moderation may contribute to effective leadership.

- Part 7: The importance of directionality in leadership, including goals, vision, and purpose.

Introduction

Culture is a mysterious, and ubiquitous force that’s integrated into all human societies, large and small, across the world. Its mystery lies in the fact that we can’t see it or touch it, that it often eludes our awareness, and yet it fundamentally shapes how we perceive, think, feel, relate, and act. Its ubiquity stems from the fact that it coordinates human activity in groups. Anywhere there are groups or societies - all but the most solitary places on earth - culture emerges. It defines social norms that promote harmony, cohesion, and stability, while also facilitating collective responses to threats. As a mechanism for coordinating human activity, and creating order, it resembles yet another ancient social phenomenon: leadership. Since culture and leadership are both social processes that serve similar functions, it seems likely they would influence each another… but how do they interact?

In this article, I’ll make the case that societal culture is an overarching and dominant social force that shapes our mental models of what effective leadership involves. In other words, societal culture writes the ‘scorecard’ we use to evaluate whether leadership is good or bad, effective or ineffective.

To explore and support this position, I’ve divided this article into two major sections.

In the first, I'll share evidence suggesting that societal culture shapes leadership. Here, I’ll define societal culture using several well-known frameworks, describe how specific leadership behaviours may vary across cultures, and present evidence that leader alignment with their societal culture improves effectiveness.

In the second section, I'll explore how societal culture remains a superordinate influence, even when leaders try to shape their own organizational cultures. I’ll discuss how founders/CEOs have a brief opportunity to shape company culture in a firm’s early stages, after which culture solidifies, and becomes less malleable. I’ll then explain how at this stage leaders need to shift towards managing and maintaining harmony between subcultures. I’ll also make the point that however much influence founders/CEOs may exert on their organizational cultures, societal culture exerts an upstream sway on the leader behaviours they choose to express, and the ones they endorse within their firm. In this way societal culture forms the foundation upon which we think about and evaluate leadership, in ourselves, and in others.

Finally, at the end of the article, I’ll offer some practical suggestions for executives on how to use the principles reviewed here to navigate challenges related to culture and leadership.

Part 1: When culture shapes leadership

Defining culture

What is culture and how should we define it?

One useful definition comes from a long-term, multi-year project investigating the relationship between culture and leadership, called the Global Leadership and Organizational Behavior Effectiveness project (or GLOBE). The initial phases of this study, which focused on defining culture, involved 17,000 managers, in 951 organizations, across 62 societies around the world.

Here's how the GLOBE project defined culture:

- Culture involves shared and stable practices, values, motives, beliefs, identities, and interpretations of significant events.

- These shared elements emerge from the common experiences of collectives.

- Culture helps social groups solve fundamental problems.

- Culture can be transmitted across generations.

Another intriguing way to define culture comes from the late Edgar Schein, a former professor at MIT's Sloan School of Management.

He claimed that culture is a response to a survival problem. He said it involves shared learning that helps the group adapt to the external environment (including threats), while at the same time coordinating and organizing internal functioning.

Another element of culture according to Schein, is that it reflects ‘what works.’ Schein contends that if a set of practices work well enough to ensure the survival and/or health of the group, they then become ‘culture,’ and are taught to others in the collective as the correct way to perceive, think, feel, and behave in response to those survival problems.

Yet another element of Schein’s definition of culture is that, while it includes observable components or artefacts (e.g., what a newcomer may see and feel when they arrive in a new country or company), and espoused beliefs and values (e.g., what people say they as group members value and aspire to), that the most important part of culture is a set of deep and interconnected assumptions about people and the world. These sink to the level of unconsciousness, and members of a culture may not even be able to articulate them if asked to do so.

A final interesting aspect of Schein’s work on culture is that he described how it could manifest below the level of a society – for example he explored organizational culture (and the multiple subcultures that can arise within it) and professional cultures (e.g., engineers, doctors, scientists, and others who experience homogenous professional training, career experiences, and socialization).

Dimensions of societal culture

Now that we have in mind a basic definition of the concept, let's explore several dimensions we might use for describing and classifying the most macro-version of it - societal culture. The three frameworks I'll describe come from Geert Hofstede, the GLOBE project, and Erin Meyer's popular book 'The Culture Map.'

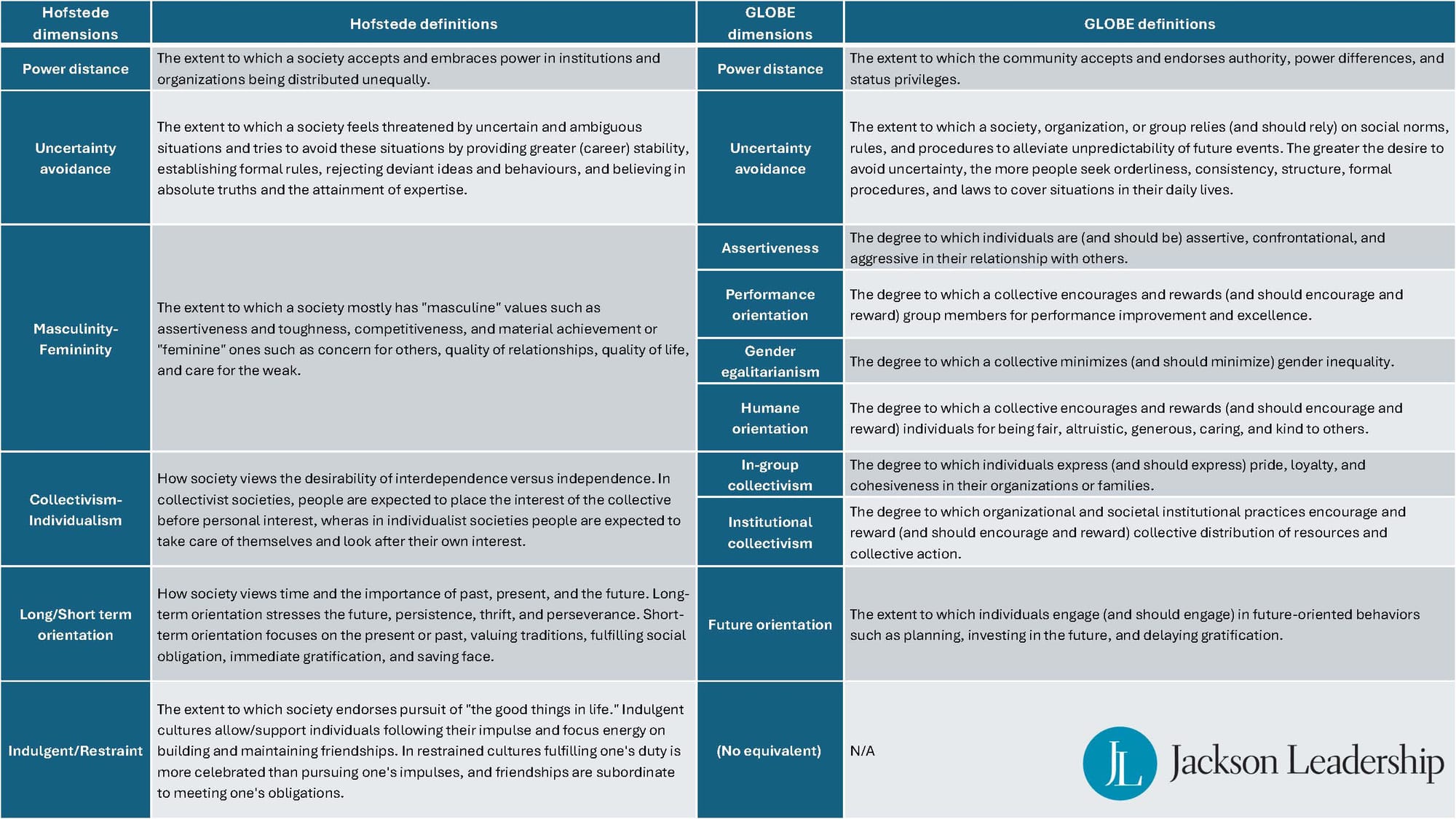

In the 1970s, Geert Hofstede collected over 100,000 surveys across 40 countries, at the multinational company IBM. He used this data to distill several dimensions which could be used to classify societal cultures all over the world.

The dimensions Hofstede distilled were as follows:

- Power distance

- Uncertainty avoidance

- Masculinity-Femininity

- Collectivism-Individualism

- Long/Short term orientation

- Indulgent/Restraint

Years after Hofstede's initial work, the GLOBE project distilled their own dimensions of societal culture, some conceptually similar to Hofstede’s framework, but with some differences:

- Power distance

- Uncertainty avoidance

- Assertiveness

- Performance orientation

- Gender egalitarianism

- Humane orientation

- In-group collectivism

- Institutional collectivism

- Future orientation

In the following matrix, I provide the definitions for the dimensions in these two frameworks, and also attempt to show the conceptual relationships between the two schemes.

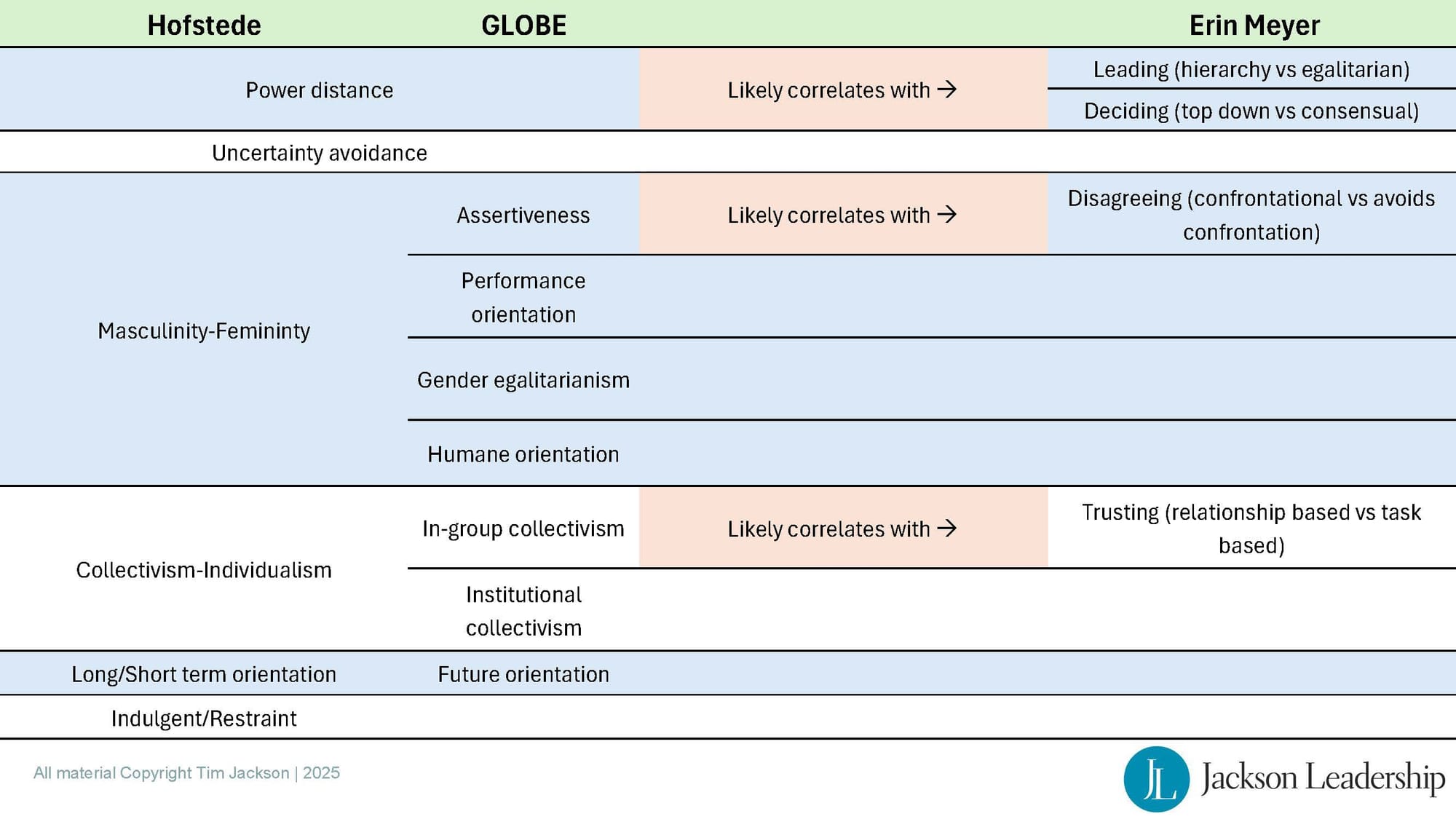

Another more recent set of culture dimensions comes from Erin Meyer’s popular and incredibly fun-to-read book titled ‘The Culture Map’:

- Communicating: differentiates cultures that demand simple, precise, and clear communication, versus ones that convey messages in indirect, sophisticated, nuanced ways (i.e., a lot of reading between the lines).

- Evaluating: distinguishes cultures that give negative feedback in direct, blunt, and honest ways, versus those that give it softly, subtly, and diplomatically.

- Persuading: differentiates cultures that persuade by highlighting facts and practical considerations first (i.e., using executive summaries and bullet points), versus those that start with theory and build towards a conclusion.

- Leading: this is equivalent to the power distance dimension articulated by Hofstede and GLOBE, and addresses society’s preference for hierarchy vs egalitarianism.

- Deciding: this describes societies based on whether they make decisions using top-down or consensual processes.

- Trusting: this differentiates societies that build short-term relationships primarily through tasks and business activities versus those that build long-term relationships through personal time spent together socializing outside of work (e.g., at meals, having drinks).

- Disagreeing: distinguishes societies based on whether they disagree in a confrontational or more harmony-seeking way.

- Scheduling: classifies societies based on being precise and organized in their use of time, versus those that are more flexible and fluid.

In the following matrix I describe how the Hofstede and GLOBE frameworks conceptually relate to each other, and how they might relate to three of Meyer’s dimensions (i.e., these are my guesses). Note, for many of Meyer’s dimensions, I'm unsure how they might map onto Hofstede/GLOBE. This is partly why I find her work interesting, because it describes cultural phenomena in an updated and original way.

Alternate models of culture

There are also some lesser-known conceptualizations of culture worth mentioning. My sense is the following could be used to describe either societal culture (which I’ve been focusing on to this point) or organizational culture. Each of these themes reflects very different underlying assumptions about people and relationships, and has different implications for leadership behaviours (as I've noted in round brackets below).

The essence of human beings and their basic motivation

Are human beings fundamentally good, evil, mixed, or neutral?

(If leaders see team members as trustworthy, they may be more likely to give them freedom and provide less supervision.)

Can human beings change, improve, and overcome any weakness or ‘badness’?

(If leaders see others as changeable, they may invest more time and energy in training, otherwise they may focus on selecting the right people.)

Relationship to the outside world

Should societies and people strive for dominance (taking control of the environment), harmony (fitting in with the environment), or subjugation (being subservient to nature, i.e., fatalism)?

(Whether a culture is dominant or harmony oriented might affect how leaders set strategy for interacting with the market and stakeholders.)

The nature of relationships

Should relationships within a culture be exploitative, surface level and transactional, or more interpersonally close?

(If a culture values close relationships, leaders may invest more time socializing and building bonds within the team prior to starting an important project.)

Different cultures like different kinds of leaders

The early phases of GLOBE involved creating a classification system for societal cultures, as described above. However another purpose of the project's early stages was to investigate whether different societal cultures preferred different styles of leadership.

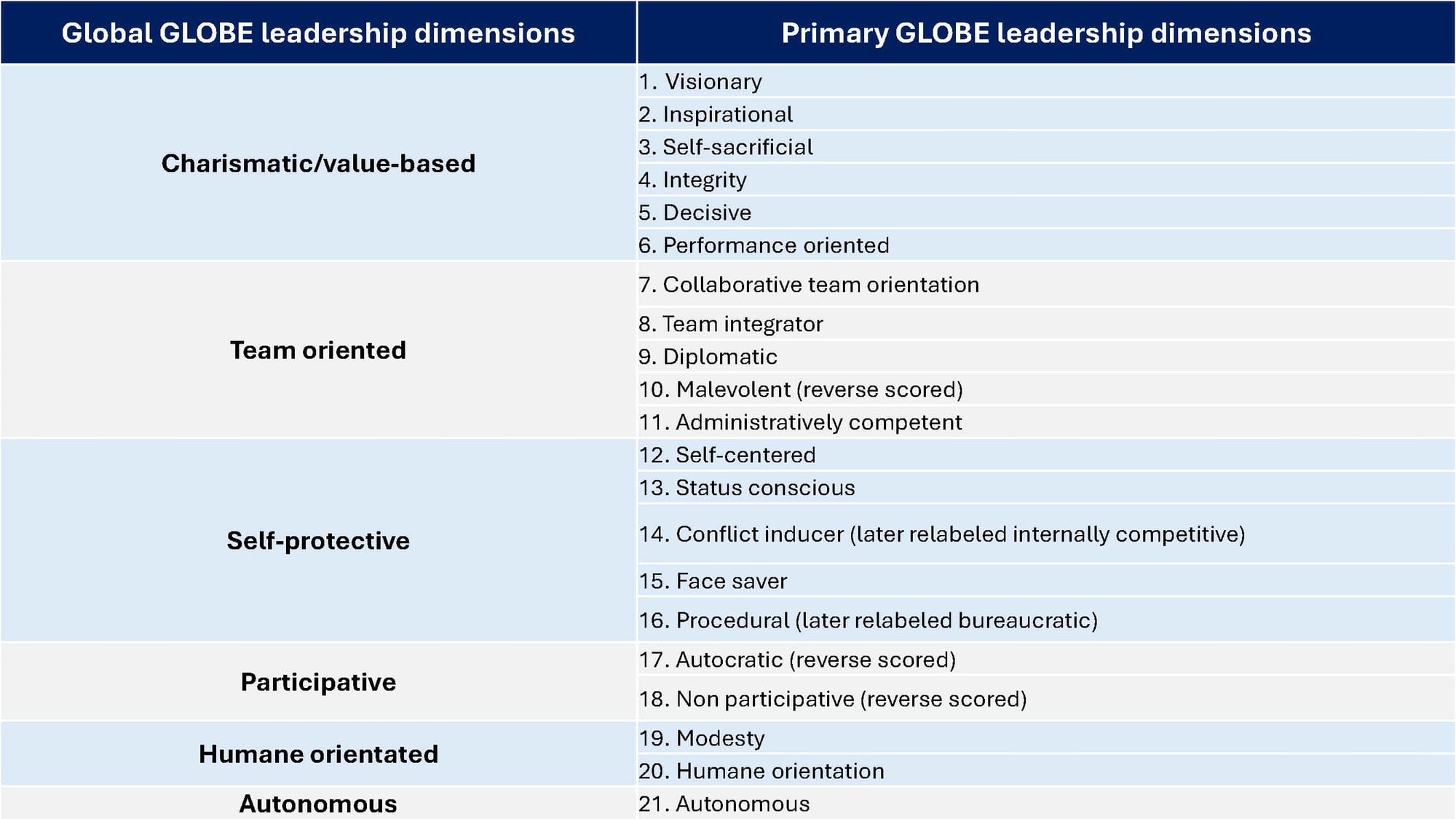

In order to answer this question, the GLOBE investigators had to create a model they could use to describe leadership all around the world.

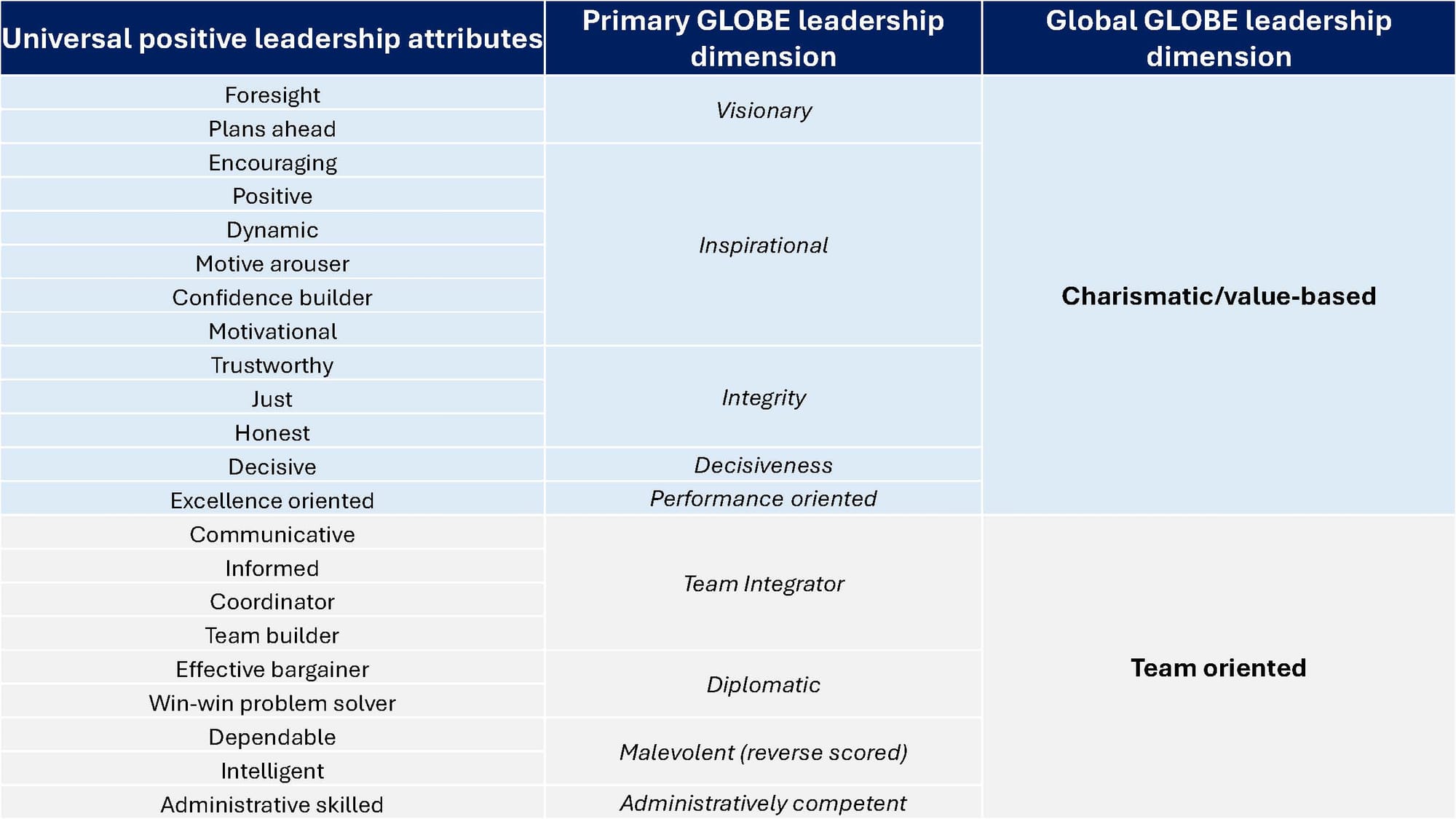

I’ve captured this leadership framework in the matrix below. It includes six global dimensions, and twenty-one facets.

Once the GLOBE researchers defined their dimensions for a) societal culture, and b) leadership behaviour, they could examine relationships between the two.

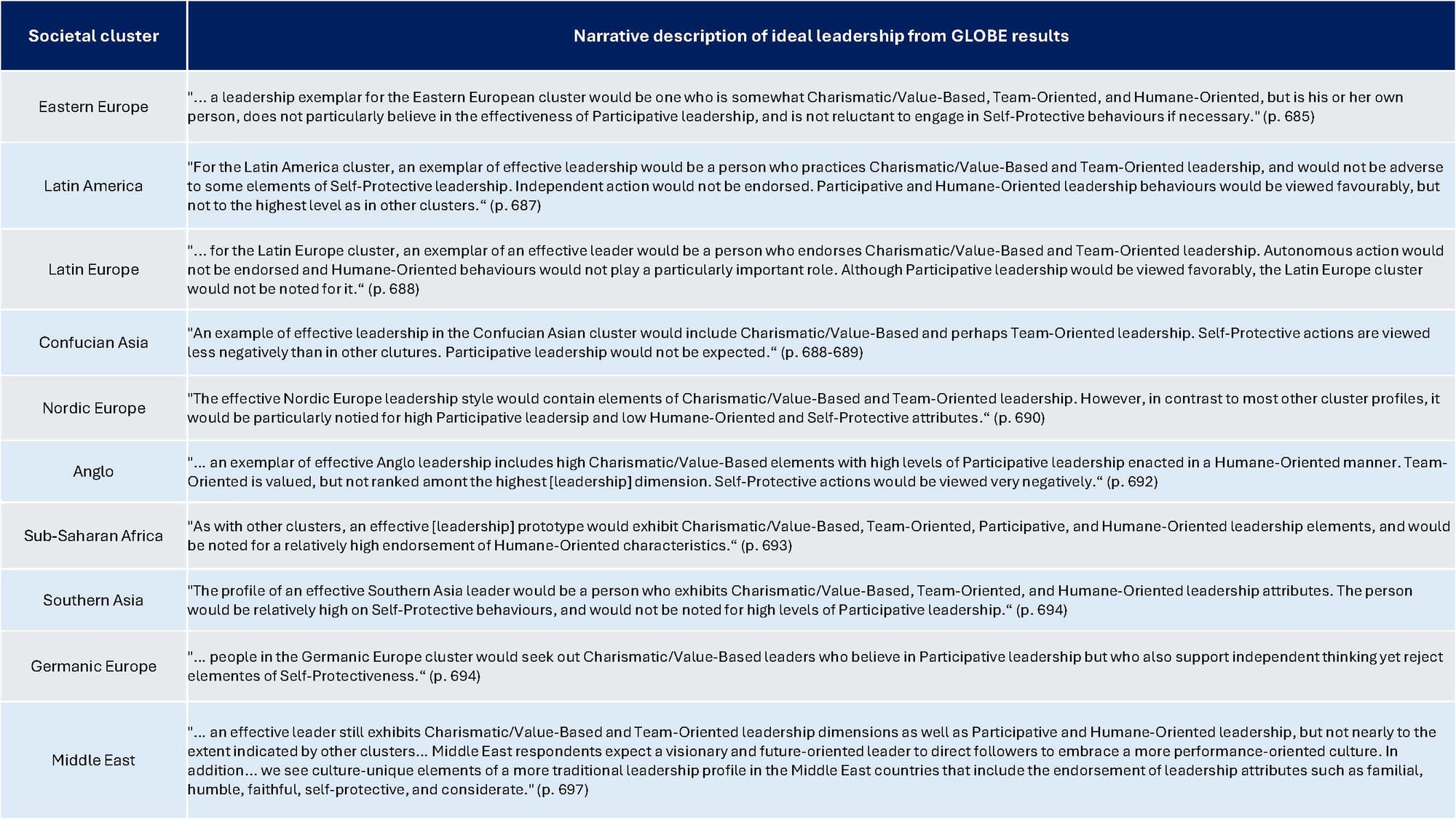

In the matrix below, I've reproduced a table from the GLOBE study results, showing how different societal clusters (i.e., groups of countries with homogeneous cultural characteristics) vary in their preferences for different leadership behaviours.

The matrix shows how different societies value different leadership behaviours, and how their 'scorecards' of leadership vary.

The letters in the matrix tell you how much members of a society think a behaviour contributes to leadership effectiveness, ranked against other societies. 'H' means a high ranking, 'M' means moderate, and 'L' means a low ranking - again, relative to other cultural clusters. In other words, this matrix highlights the variation in what people value in leaders, across cultures.

To go through an example, take a look at the Anglo cluster, which includes Australia, Canada (English speaking), Ireland, New Zealand, South Africa (white sample), the United Kingdom, and the United States. In this Anglo cluster, people think that Charismatic/Value-based, Participative, and Humane behaviours (each labeled with a large 'H') all contribute more to effective leadership, compared to other cultural clusters. Also in the Anglo cluster, people tend to be much less enthusiastic about Self-Protective behaviours (labelled with a little 'L'), again compared to other cultural clusters.

The display shows some interesting cultural variation in leadership preferences. People in the Middle East (i.e., Egypt, Kuwait, Morocco, Qatar, and Turkey) rank 'Self-Protective' leadership much higher (which equates to a more neutral view of this leadership style), and ranks traditional Western stereotypes about leadership (e.g., charisma, team orientation, and participative leadership) as less favourable though still positive.

Also, people in Eastern Europe (Albania, Georgia, Greece, Hungary, Kazakhstan, Poland, Russia, and Slovenia) and Germanic Europe (Austria, Germany, the Netherlands, and Switzerland's German speaking culture) rank Autonomous leadership (i.e., the leader is independent, individualistic, and acts without relying on others) as much more favourable than other societies.

Other ways to examine cultural differences in leadership preferences

Another way to digest the differences in leadership 'scorecards' across cultures is to review the GLOBE's descriptions of the ideal leader in each cultural cluster. See the matrix below for these summaries.

Yet another way to parse the GLOBE results is to examine how the scorecards for effective leadership vary across countries who have particularly high scores on three important culture dimensions: Power Distance, Uncertainty Avoidance, and Individualism.

In high Power Distance countries (e.g., Russia, India, Nigeria), team members would more than likely prefer their leaders be status conscious, class conscious, elitist, and domineering.

In high Uncertainty Avoidance countries (e.g., Switzerland, Sweden, Singapore), team members would prefer their leaders be low risk taking, habitual, procedural, formal, cautious, and orderly.

And in high Individualism countries (Denmark, New Zealand, Netherlands), team members would more often endorse leader behaviours like being autonomous, unique, and independent.

A final way to absorb the GLOBE's findings is to examine the leadership attributes that vary the most across cultures, in terms of whether people believe they contribute to effectiveness or not:

- Status conscious

- Bureaucratic (labeled procedural in an earlier phase of the GLOBE study)

- Face saving

- Internally competitive (labeled conflict inducer in an earlier phase of the GLOBE study)

- Autonomous

- Humane

- Self sacrificial

Culture shapes the expression of the scorecard

Interestingly, even when members of different cultures agree that a principle is critical for leadership effectiveness, they may differ the way they express it.

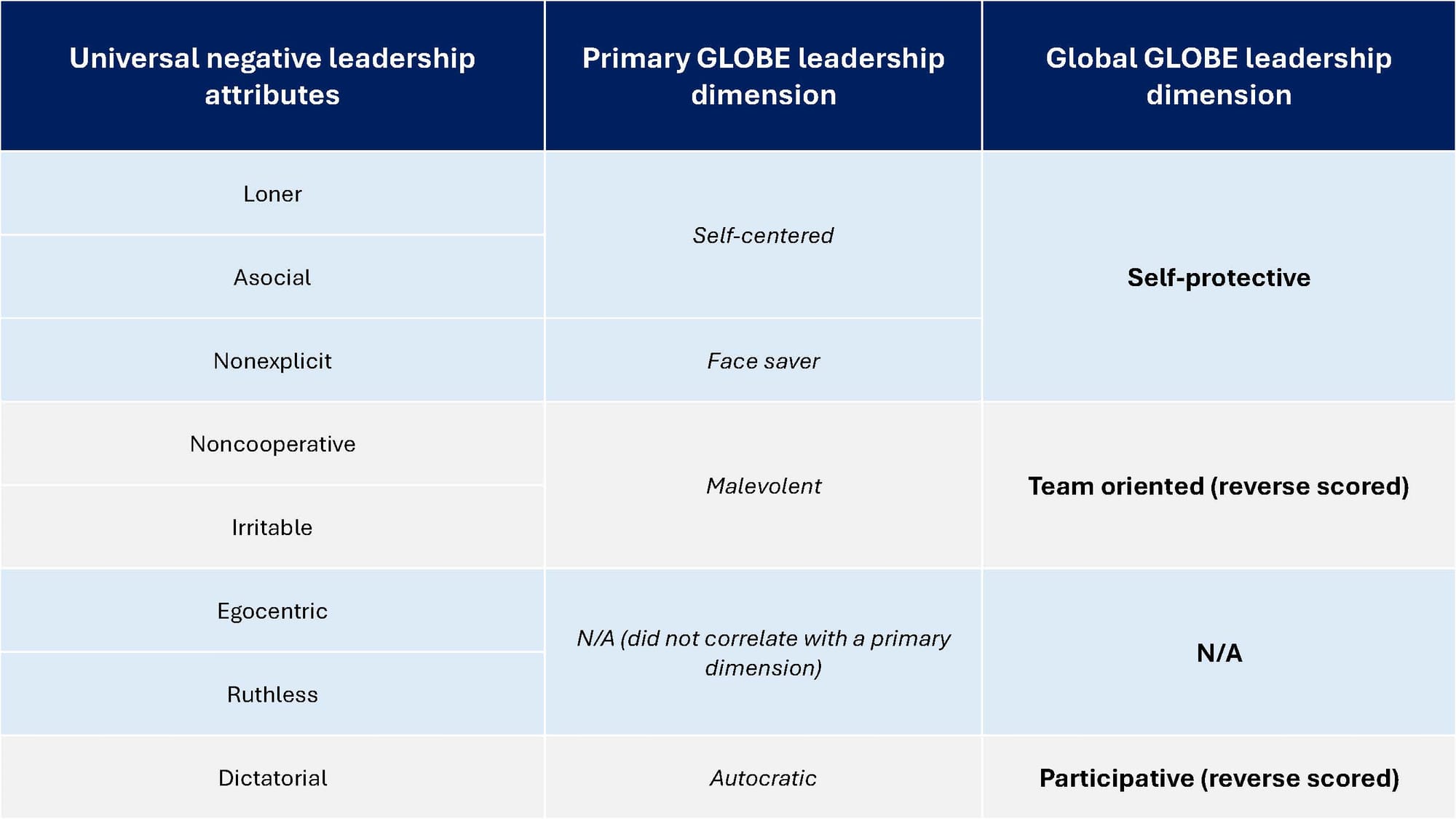

For example, the GLOBE study found that several 'universal' leadership behaviours are endorsed as positive, or negative, by most or all of the societies they studied. See below for a list of leadership attributes that are generally viewed as positive or negative.

However, even with universal principles, culture can still influence unique expressions of these behaviours.

‘Simple universals’ are those where the principle and the enactment are the same across contexts. By contrast ‘variform universals’ involve cases where the principle is shared across contexts, but the enactment differs.

So for example, two cultures may both endorse charismatic and value-based leadership, which involves articulating a vision. In the more ‘Assertive’ of the two societies leaders may tend to express that vision in an aggressive way using language about dominating competitors. By contrast in the more ‘Humane’ of the two cultures leaders may express their vision using a collaborative tone, invoking the need to strive for harmony with stakeholders and communities.

Therefore, culture shapes the scorecard for effective leadership in multiple ways, by influencing both it's underlying principles, and also the unique behaviours used to express or operationalize it.

Leader alignment with culture improves effectiveness

A later stage of the GLOBE study provided further support that culture shapes our 'scorecards' for leadership effectiveness, by showing that it's critical for leaders to align with culturally-determined criteria.

This later stage of GLOBE was as comprehensive as earlier ones, and involved 1060 CEOs, and more than 5000 of their team members, across 24 countries.

The investigators evaluated leader effectiveness in two ways: first, using a measure of each CEO’s top management team ‘dedication’ (a composite of commitment, effort, and team solidarity); second, using multiple measures of overall firm performance.

The investigators found that leaders who most aligned their behaviours with the cultural values of the societies they lived in were rated as most effective, and produced the best objective results in terms of their company’s performance.

Interestingly, the most successful CEOs over indexed on their cultural alignment, expressing more of the behaviours than was average or typical in their society.

By contrast, poorly performing CEOs displayed fewer culturally aligned leadership behaviours.

These results suggest that it's critical for leaders to align with the 'scorecards' for leadership within the culture they're working in. Once again, societal culture shapes the criteria, and leaders must adapt to those demands in order to be perceived as effective.

Part 2: When leadership shapes (organizational) culture

Does culture always shape leadership, or can leaders reverse this process and shape culture?

Until now I’ve described how societal culture exerts a powerful, ever-present, yet hard-to-detect influence on the ‘scorecard’ we use to judge effective leadership.

There are cases however, when leaders can shape culture – but when I refer to culture here, I mean the local organizational culture around them. Specifically this can occur when founders or CEOs mold the culture of their early-stage companies.

Edgar Schein described in his book ‘Organizational culture and leadership’ how founders or CEOs have a brief window during which they can definitively shape organizational culture, and which opens during the earliest stages of a company’s life cycle.

During this formative period, founders/CEOs define literally every facet of the company and how its employees interact, all of which collectively create culture. They influence the vision, strategy, priorities, goals, structure (including who has more vs less power and resources), personnel (who’s hired, promoted, or excommunicated), processes, metrics, preferred ways of relating to one another, rewards/punishments, and even stories/myths that reinforce key values or principles.

Put in more concise terms, Schein would argue that the founder/CEO creates a vision and a set of values, and if they ‘work,’ and members of the organization see that approach contributes to the survival and health of the organization, then culture forms.

Put even more simply, if the approach of the founder/CEO works, culture coalesces around that approach, and then members of the company attribute ‘leadership effectiveness’ (after the fact) to the founder/CEO.

It’s important to note, however, that the leader’s chance to shape organizational culture is ephemeral. After the company reaches what Schein calls mid-life, achieving a degree of success, size and maturity, culture solidifies, and becomes more durable. At this stage, the leader will not be able to influence the culture easily. Schein might say that at this moment, the organizational culture manages the leader more than the reverse, that culture is now the 'cause,' and leadership the 'effect.'

Schein says that at this point of maturity, the leader’s core role is to manage organizational culture, including creating harmony between multiple subcultures. These subcultures can arise in different functions (e.g., sales vs marketing vs operations vs manufacturing), divisions (e.g., semi-independent entities within the business, sometimes divided by customers, or geography), or even professions (e.g., engineers vs scientists vs finance etc). A clear assertion running throughout Schein’s work is that organizations who better manage their subcultures will tend to be more effective. His contention is that very different subcultures can coexist peacefully, however if the friction between them becomes too great, it creates an undertow of dysfunction that can compromise the organization's ability to adapt to the external environment. Schein is also clear that it’s the leader’s role to create harmony between subcultures, and that they shouldn’t outsource this responsibility to HR or a consultant.

I want to make a key point here, that even when we think leaders step forward in an agentic way to shape their organizational cultures, societal culture still exerts a quiet, but unmistakable authority. Remember, founders/CEOs of early stage companies are themselves shaped by the societal cultures they’ve been raised in and live in. Leaders’ values, preferences, views, and assumptions about how to work all emerge, in part, from the societal culture they're steeped in. So a leader will instill their personal imprint onto the organization they’re building – yes - but upstream of that, societal culture has already imprinted itself on the leader. Therefore, you could say that societal culture influences founders/CEOs, who in turn shape the cultures of their new companies, and the ‘scorecards’ for what effective and ineffective leadership looks like within them.

Another final point is that Schein argues that organizational cultures need to exist in harmony with the societal cultures surrounding them. If true, this principle further suggests societal culture always frames and constrains organizational cultures, and the leadership behaviours championed within them.

Practical recommendations

Thinking about societal culture and leadership...

- Defer and adapt to societal culture: If you’re leading in a different societal culture than your own, the culture of the place you're in has primacy - you can’t outsmart it or out maneuver it. It will determine how others judge your leadership effectiveness (i.e., the scorecard). To be successful, you need to understand the culture you’re embedded in, and align your leadership to it. Culture is more powerful than your individual leadership skill, and you need to show some deference towards it.

- Use education, facilitated discussion, and team-level agreements to support multicultural teams: If leading a multicultural team, set up a process for learning about culture, talk about what differences exist within the team, and then develop strategies and tactics to navigate them. In her book, Erin Meyer suggests that simply educating team members about various cultural dimensions (e.g., like Leading, Deciding, Disagreeing, from her framework), and discussing how members differ on them, laced with some humility and willingness to joke about your own culture, builds a facility for people from different backgrounds to work better together. Edgar Schein advocates something similar, with his facilitated ‘cultural island’ exercise. This involves asking team members to share personal experiences of their home culture, by describing how they would handle two key situations in that milieu: a) confronting authority, and b) building trusting relationships. (For those interested, I will write an article in the near future explaining Schein’s ‘cultural island’ technique in more detail.) Meyer also suggests creating team-level agreements to foster a local, neutral team culture. This could involve coming to an agreement within the team, in advance, on a decision making process (top down or egalitarian), on how to debate (confrontational vs not), or on how to handle time (flexible or precise). A team could also create a charter for itself, which articulates a local, culturally neutral set of norms that the entire team will adhere to.

- Read ‘Culture Map’ by Erin Meyer: If you are embarking on an expat assignment, one of the best things you could do to prepare yourself to deal with cross-cultural challenges would be to read Erin Meyer’s book ‘The Culture Map.’ It’s accessible, practical, and full of examples and stories derived from her considerable teaching and consulting experience. As you read you feel like you’re trailing after Meyer on her globetrotting teaching and travel adventures, and there’s so much good storytelling that you forget how much you’re learning. Her model of culture also gives you a sense of behaviours ‘close to the ground,’ those most likely to arise in business settings. This is a more practical starting point for learning about culture compared to trying to apply the Hofstede or GLOBE dimensions or findings. Meyer doesn’t get too abstract when she describes cultures, which I think makes her model more useful to executives. If you're interested in the intersection of culture and leadership, or just culture in general, it's a great start.

Thinking about organizational culture and leadership…

- The window to shape organizational culture is only open for an instant: If you’re a founder or CEO, remember that you can influence organizational culture the most during the very early stages of your firm’s existence. Once the organization reaches maturity or mid-life, organizational culture in Schein’s words “becomes more of a cause than an effect.” At that point you as the leader will be constrained in shaping the company’s culture, and if you decide to change it, you should only incrementally evolve one or two components at a time.

- In mature organizations, leaders need to manage subcultures: If you’re a senior leader or CEO in a company that’s reached maturity or mid-life, one of your main roles is to manage and create harmony between the different subcultures. It may help you to spend time defining the subcultures you manage (e.g., functions, divisions, professions), assessing how harmoniously they’re working together, and then asking what you can do to foster smoother functioning between them.

- Tether culture change to a change goal: If you’re a leader who wants to change your organizational culture, consider the following process advocated by Schein:

- First, define your change goal. What do you want the company to do differently? As Schein suggests, define that change goal without the word culture, to help focus on the concrete change in the organization that you want to realize. And go beyond abstractions like ‘improve XYZ’ - be specific about the exact change you want. Culture change untethered to a change goal, Schein says, becomes overly complex and participants can feel the exercise is pointless.

- Second, consider how the existing culture helps or hinders the path to achieving that goal.

- Third, choose to change one or two fundamental assumptions embedded in the culture that will facilitate achieving the change goal. Schein says trying to change too many elements of culture at once will risk failure.

Thinking about leadership...

- Use the universal leadership attributes to check your effectiveness: I realize that culture can influence the expression of universal principles, but nonetheless, it may still be useful to use the set of universal positive and negative attributes (mentioned above) as a checklist to assess your own leadership effectiveness. Are you demonstrating all the positives? Are you avoiding all the negatives? This list is a valuable competency model that leaders can use to self-assess their own style.

Conclusion

In one of the early chapters in Meyer’s book ‘The Culture Map,’ she explains that in some cultures, communication can be explicit and direct, yet in others, particularly in Asian countries, it can be much more nuanced and indirect, requiring the listener to ‘read between the lines.’ She quotes a Japanese executive who attended one of her workshops, and said that in his country, they’re taught to ‘read the air’ or in other words, to interpret all the subtle, hidden and implied meanings the speaker might convey. Meyer uses this concept to illustrate how communication differs across societies, but it strikes me that the metaphor also works for describing culture in general. Culture is like air in the sense that it’s all around us, it’s easy to miss, and it’s fundamental to (social) life. And yet culture does more than that - it also changes us, including our sense of what we like and don’t like. It gently imposes on us a scheme or scorecard for interpreting and evaluating the leadership behaviours that we express, as well as those we observe in others. It is superordinate, in that even when leaders think they’re transmitting their idiosyncratic beliefs and values to others, culture has already stopped by for a visit, and in the process shaped what they think makes a great leader. In the end, Meyer’s metaphor may work best as advice for leaders seeking to adapt to culture: perhaps the best they can do is to squint hard in order to ‘read the air,’ to discern the faint but unique cultural rules and fault lines all around them, and to learn to let those inherited ways of organizing human activity guide their actions.

Further reading

'The Culture Map' by Erin Meyer

'Organizational culture and leadership' by Edgar Schein

Leadership, culture, and globalization - book chapter written by Deanne Den Hartog and Marcus Dickson, in 'The Nature of Leadership' edited by David Day and John Antonakis.

GLOBE project website - includes list of books and publications, and descriptions of measures, methods, and results.

Music

Los Angeles is an iconic city, and one that often appears as a central character in many songs and movies. Based on this, I recently asked some friends of mine, who had lived in Los Angeles for 4 years, "what's your favourite song about LA?" Their response was "LA" by Randy Newman, and "Babylon Sisters" by Steely Dan.

For my part, I have three favourite songs about LA, and this is one of them...

John Mayer, performing 'In Your Atmosphere' in 2008... in LA of course.

Tim Jackson, Ph.D. provides advisory and deep expertise on executive leadership development, to dynamic and high performance organizations.

Tim's services include in-depth executive assessment using interviews and gold-standard qualitative data analysis techniques; executive advisory and coaching rooted in his deep expertise of the drivers of leadership effectiveness; workshops built with evidence-based data and models that transfer high-quality knowledge, and enhance the impact of participants; and facilitated sessions that create dialogue and conversation among senior leaders, in a safe environment that promotes shared learning.

Throughout his 18-year career, Tim has worked with a wide variety of clients, including CEOs, executives, managers, and individual contributors; leaders located in Canada, the US, Europe, and China; individuals spanning 11 different industry sectors and every key functional area; and those driving major change inside private-equity owned businesses.

The following are examples of how Tim has delivered value to his clients: he assessed and coached 28 leaders in a large Canadian CPG company over a 5 year period, including preparing high potentials for promotion and helping derailing leaders course correct; he coached senior leadership team members and middle managers in a global chemical company to navigate dynamic change resulting from the largest acquisition in their history; and he provided assessment, coaching and advisory support to the CEO of a Canadian ‘supercluster,’ a federally-funded accelerator of strategic economic activity (this cluster received renewed funding in early 2023).

Tim has published his ideas about leadership in various outlets, including The Globe and Mail, Forbes.com, several HR trade magazines, and peer-reviewed journals. He also writes original articles about leadership topics in his newsletter at www.timjacksonphd.com. He has also shared details of his practice at leading conferences like the Society for Industrial and Organizational Psychology.

Tim has a Ph.D. in Industrial/Organizational Psychology from Western University, where he explored the drivers of leadership effectiveness in both his Master’s and Dissertation-level research. He and his family are based in Toronto, ON.

Please feel free to contact Tim with your feedback about this site, questions about his services, or to share your own ideas about leadership in organizations.

Email: tjackson@jacksonleadership.com

Phone: 647-969-8907

Website: www.jacksonleadership.com

Newsletter: www.timjacksonphd.com

Member discussion