"Pretty please, with sugar on top": Four ways leaders can gain permission to challenge for high-performance

Introduction

Three years ago I started a research project which involved interviewing 37 executives to ask them how they challenge for high-performance without ‘breaking people’ (i.e., damaging motivation or fracturing relationships).

In the last year and a half, I’ve used this newsletter as a forum for drip-feeding out some of the more interesting results. The topics I covered included gaining permission or consent to challenge, planning challenges to ensure adequate rest/recovery, avoiding relentless goal pressure, signaling to help others interpret a challenge as constructive, challenging more senior leaders, the three kinds of tension to apply when challenging (interactional, goal, and system), and lingering questions about the three kinds of tension.

In this article, I’d like to elaborate on one interesting idea that’s emerged from this research, which is that gaining permission first allows leaders to challenge more vigorously without risking offending the other person.

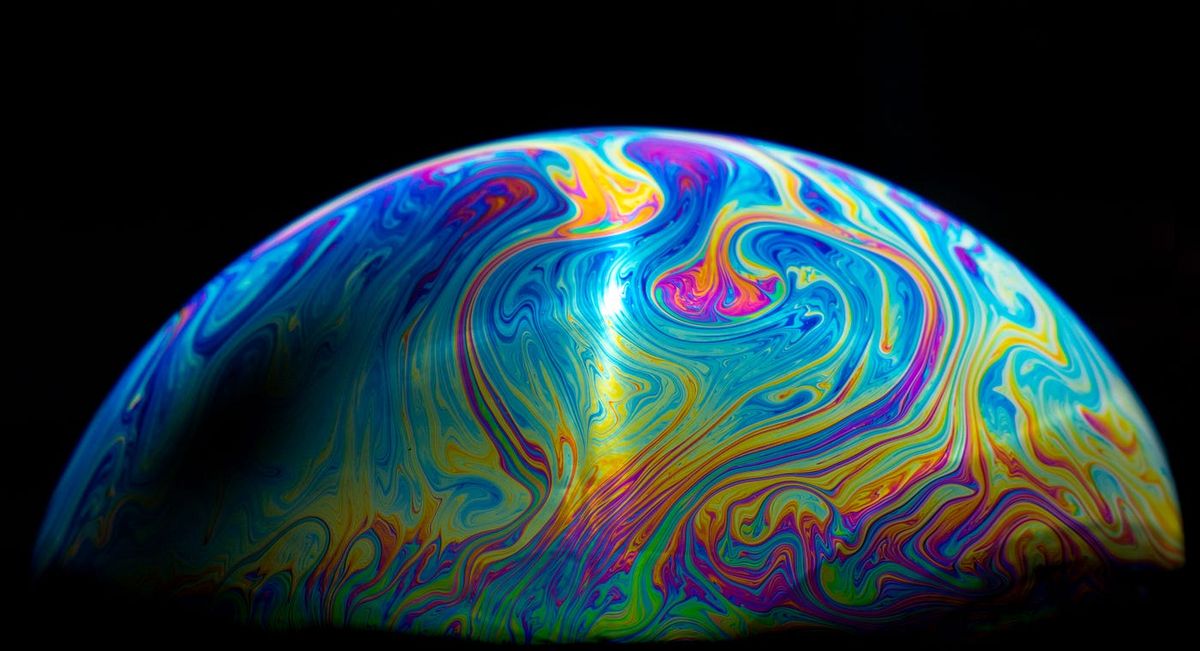

In my mind, when a leader gains this consent or permission to challenge, it allows them and the team member on the receiving end to enter a kind of high-performance bubble. Inside this rarefied space, new social rules apply. No longer does a leader need to worry so much about alienating others, or damaging relationships. Rather, inside the bubble they can challenge all they want, push people to the limit of their capabilities, while feeling secure that such a challenge is welcome and isn’t infringing on the autonomy of the other person.

See this article from Oct 2023 for more on the idea of gaining permission to challenge.

Ok, so if gaining permission allows leaders to challenge for high-performance more vigorously, how do you ‘gain permission’?

Here I’ll outline four different approaches.

Four ways leaders can gain permission to challenge for high-performance

- Gaining consent: This first one is simple, and involves just asking the team member if they are willing to be challenged. This is an explicit request, and happens during an interpersonal exchange. “I was wondering if I could challenge you more on this goal. Would that be ok? If you give me permission, I’ll push you a bit harder than you might push yourself, but I will support you through that process, and in the end I think this could produce some great results.”

- Permission structure: This involves leaders creating a set of norms within the team that endorses or normalizes challenging. In effect you create a structure, process, or even culture that says “it’s ok to challenge, it’s not meant to offend, it’s just part of how we function as a team.” A permission structure can take many forms: establishing meeting objectives or ground rules which endorse challenging for high-performance, creating a team charter that enshrines and normalizes challenging, creating a decision-making process that requires challenging before reaching closure, or developing a meeting checklist that includes challenge behaviours as a necessary requirement. In essence, the permission structure is a set of ground rules or agreed-upon norms which help people in the team interpret challenges (from the leader, or even from other team members) in a common and constructive way.

- Relational permission: The first two principles were somewhat explicit, the next two are more implicit. Relational permission emerges when a leader has a strong and durable relationship with one of their team members. In those cases, the relationship itself gives unspoken and implicit permission for the leader to challenge that team member to a greater degree. Did you ever have a coach that you had a close relationship with? Did that bond enable them to challenge you without causing offence? When the relationship is close, the person receiving the challenge tends to interpret the ‘push’ in a more benign way, saying to themselves “oh, I know John, I know he has good intentions, I trust him, and if he thinks I can achieve more, I’m willing to believe him and try.”

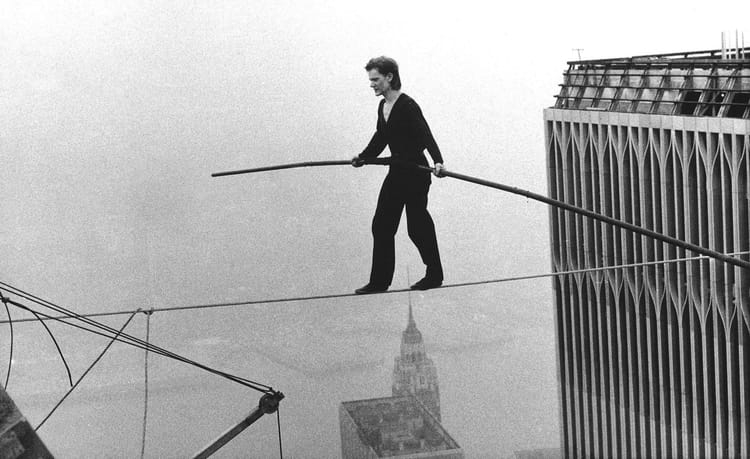

- Identity permission: The last way for a leader to gain permission is through developing a high degree of credibility, by virtue of their experience, achievements, or reputation. If a leader doesn’t have credibility in your eyes, and asks you to do something really difficulty, you may balk – “who is this guy, and who does he think he is?” By contrast if the leader challenging you is the CEO with a stellar history of business success, you might think “I’m scared to do this, but she has so much experience that maybe I should trust her, and stretch myself beyond what I think I can do.”

Just a couple of other minor points. First, the process of gaining permission can also occur in a way that reverses the power dynamic, with the team member seeking consent from the leader. Sometimes team members need to challenge upwards, when they want to spark change in the organization. But this can be risky, since the leader has a power advantage over them, and can influence their compensation and job security. A safe approach might be for the team member to ask for permission to challenge the position or perspective of the leader, before doing so. If the leader grants it, the team member can feel free to speak their mind without negative repercussions.

Finally, some of these principles might work in a sequence. For example, as suggested by one executive I spoke with, when challenged, team members might first consider if they have a strong relationship with the leader; if they don’t, they may next default to considering the reputation/credibility of the leader when determining whether to accept their challenge.

Practical application

The next time you want to challenge your team, consider setting up a permission structure first. Again this could be a team charter, a decision-making process, a set of meeting objectives or ground rules, or some kind of checklist. Try to create a cultural mechanism that endorses, normalizes, and ‘makes ok’ the use of challenging. The structure should help team members interpret any challenges – from the leader or from other teammates - as constructive and inoffensive.

When you want to challenge the team for higher performance, ask permission first, either from the collective as a whole, or from individual members. This is a simple and risk-free step – if they refuse, no harm done; if they accept, you can ratchet up the demands and see how much you can achieve together.

Over the longer term, think about ways to a) build stronger relationships within your team, and b) establish your credentials as an effective leader. Both should maximize the chances that others stay receptive to your challenges. If you’re a new leader, try to find ways to signal to your team what you’ve accomplished in the past, so they trust you when you want to nudge them for higher performance.

Music

Tim Jackson, Ph.D. provides advisory and deep expertise on executive leadership development, to dynamic and high-performance organizations.

Tim's services include in-depth executive assessment for development; one-on-one executive advisory rooted in his deep expertise of the drivers of leadership effectiveness; workshops on a variety of leadership topics built with evidence-based data; and facilitated sessions that create dialogue among senior leaders on important leadership themes, in an environment that promotes shared learning.

Throughout his 18-year career, Tim has worked with a wide variety of clients, including CEOs, executives, managers, and individual contributors; leaders located in Canada, the US, Europe, and China; individuals spanning 11 different industry sectors and every key functional area; and those driving major change inside private-equity owned businesses.

The following are examples of how Tim has delivered value to his clients: he assessed and coached 28 leaders in a large Canadian CPG company over a 5 year period, including preparing high potentials for promotion and helping derailing leaders course correct; he coached senior leadership team members and middle managers in a global chemical company to navigate dynamic change resulting from the largest acquisition in their history; and he provided assessment, coaching and advisory support to the CEO of a Canadian ‘supercluster,’ a federally-funded accelerator of strategic economic activity (this cluster received renewed funding in early 2023).

Tim has published his ideas about leadership in various outlets, including The Globe and Mail, Forbes.com, several HR trade magazines, and peer-reviewed journals. He also writes original articles about leadership topics in his newsletter at www.timjacksonphd.com. He has also shared details about his practice at leading conferences like the Society for Industrial and Organizational Psychology.

Tim has a Ph.D. in Industrial/Organizational Psychology from Western University, where he explored the drivers of leadership effectiveness in both his Master’s and Dissertation-level research. He and his family are based in Toronto, ON.

Please feel free to contact Tim with your feedback about this site, questions about his services, or to share your own ideas about leadership in organizations.

Email: tjackson@jacksonleadership.com

Phone: 647-969-8907

Website: www.jacksonleadership.com

Newsletter: www.timjacksonphd.com

Member discussion